Thousands attended the funeral of former Provisional IRA member, Bobby Storey, causing much controversy owing to the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions

Opinion: paramilitary funerals were always a focus of controversy in Northern Ireland during the Troubles

By Maggie Scull, Syracuse University London

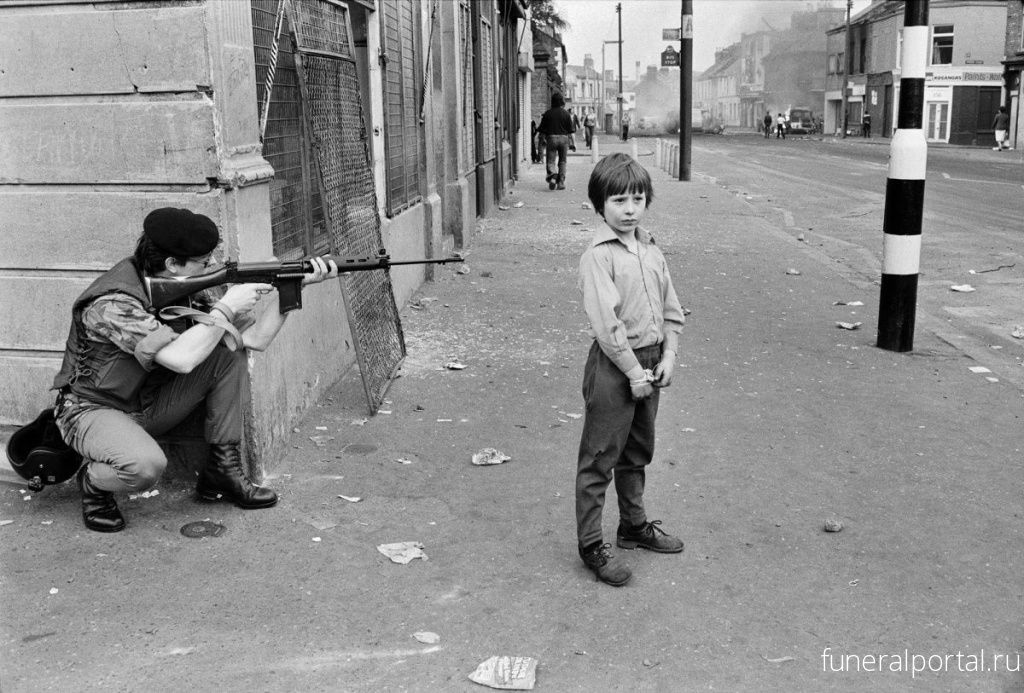

Throughout the Troubles, paramilitary funerals were a focus of controversy in Northern Ireland. Bobby Storey's recent funeral shows powerful continuities with the past, but also demonstrates just how far behind the Troubles now are. While paramilitaries used these funerals to send powerful political messages, there have always been important differences between republican and loyalist funerals, all of which point up the complexity of the relationship between politics and religion in the conflict.

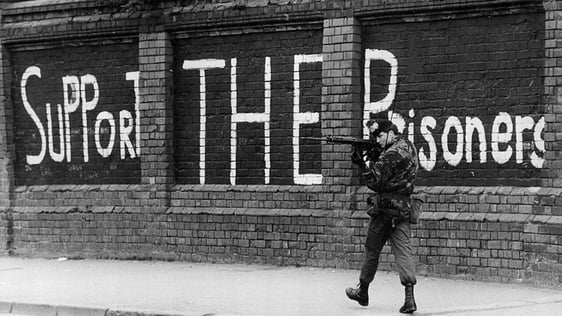

On May 7th 1981, an estimated 100,000 people attended the funeral of Provisional IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands. Film footage and newspaper reports of the event were seen around the world bringing international attention to the republican cause. In response, British security forces increased their presence at later republican funerals in an effort to curb the publicity and control the pageantry. This also often led to violent clashes between mourners and the police.

From RTÉ Archives, Forbes McFall reports for Today Tonight on Bobby Sands' funeral in Belfast in 1981

During the Troubles, loyalist and republican organisations capitalised on the nature of ceremonial funeral traditions to amplify their messages. Funerals provided one of the few opportunities for legal gatherings as the notion of every society having the right to bury their dead prevailed.

However, these funerals typically took on an overt military theme. They often included a specific non-state flag, military uniforms, a guard of honour, and a gun salute. This served many of the same purposes of funerals for conventional military organisations: to sustain morale, inspire new recruits, and show that volunteers' contributions were suitably honoured and valued.

Loyalist and republican funerals allowed a public display of strength by an illegal organisation and were often used to demonstrate levels of community support. For example, an IRA funeral was an IRA event, not that of its political wing Sinn Féin. These funerals provided rare public occasions for gatherings that could be directly associated with the paramilitary organisation and openly celebrate it. Nationalist and unionist politicians struggled to be heard as they attempted to use the platform of funerals to denounce paramilitary violence.

From RTÉ Archives, RTÉ News report on the killing of two undercover British soldiers at the funeral of IRA member Kevin Brady in 1988

Religious organisations also struggled to handle with these events. In the context of Northern Ireland, paramilitary funerals and religious responses to them highlight the entangled nature of religion, identity, and politics. Religious actors who ministered and conducted paramilitary funerals were regularly accused of condoning, if not actively supporting, violence.

The differing Catholic and Protestant practices and theologies around death, funerals, and the afterlife were often misunderstood by the other side and the very specific circumstances in Northern Ireland during this period further exacerbated tensions. For Catholics, funerals are a religious rite with the individual judged when they meet their maker and not by those on earth. Therefore, it was difficult for the Irish Catholic Church to make that judgement and deny republicans a Catholic funeral and Requiem Mass. For example, in the late 1980s, Bishop Edward Daly, of Derry, attempted to ban deceased bodies of republican paramilitaries being present at Requiem Mass but quickly had to reverse his decision.

https://www.rte.ie/archives/collections/news/21267090-ban-on-ira-funerals-lifted/ From RTÉ Archives, Jim Dougal reports for RTÉ News on Bishop Edward Daly's 1988 decision to lift a ban on IRA funerals

That's not to say there weren’t differences within the Catholic Church itself over history and religious practice. Republican funerals and the issue of excommunication were key challenges the Irish Catholic Church faced throughout the conflict with pressure coming not only from non-Catholics, but also from the English and Welsh Catholic Churches.

Loyalist funerals did not directly connect the Protestant churches with paramilitarism in the same way that republican funerals did with the Irish Catholic Church. There was not one Protestant church garnering all of the focus. Loyalists could also privately approach selected ministers, many non-mainstream pastors, to ask whether they would officiate a service whereas the Catholic priest would not have had the same choice.

Funerals have always proved crucial to sustaining the republican tradition

Furthermore, loyalist funerals could occur in the home with a procession to the graveside, bypassing a church service altogether. While they did not attract the same level of security presence or violence seen at some republican funerals, there were occasions when tensions spilled into attacks, as seen after the funeral for Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) member Brian McCallum in 1993.

The heavy security presence seen at republican funerals after the 1981 hunger strikes undoubtedly coincided with an increase in violence, though clashes between mourners and the police was not a new thing. However, it took an unprecedented three days to bury Provisional IRA member Lawrence 'Larry' Marley in 1987, as the RUC blocked attempts to remove Marley’s remains from his North Belfast home.

From RTÉ Archives, Michael Fisher reports for RTÉ News on the 1987 funeral of Larry Marley

Since the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, high profile funerals of former loyalist and republican paramilitaries have usually passed off peacefully and also seen former rivals paying their respects. Among the thousands of mourners attending the 2007 funeral of former UVF member and Progressive Unionist Party (PUP) politician David Irvine were the chief constable of the RUC, Hugh Orde, the Irish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Dermot Ahern, Sinn Féin politician Gerry Adams, and the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, Peter Hain.

Similarly, in 2017, the funeral of republican Martin McGuinness saw in attendance former US President Bill Clinton, as well as Arlene Foster, leader of the DUP and Northern Ireland's First Minister. Both Ervine and McGuinness were fervent supports of the Agreement and cross-party attendance at their funerals demonstrated commitment to the peace process.

From RTÉ Radio 1's Drivetime, Sinn Fein's Mary Lou McDonald on the ongoing controversy around Bobby Storey's funeral, social distancing restrictions and Sinn Féin

Of course, there are still exceptions as has been seen recently, in the case of the Sinn Féin activist and former Provisional IRA member, Bobby Storey. Thousands attended his funeral, causing much controversy owing to the Covid-19 pandemic restrictions that no more than 30 people be permitted to gather at the graveside. Although unionists, and many voices in the media, have argued the funeral is a flagrant violation of the coronavirus regulations, Sinn Féin has argued that criticism of the numbers at the funeral should be seen in an anti-republicanism context.

At the time of writing, First Minister Arlene Foster has asked the Stormont Assembly to gather and debate a motion calling for Sinn Féin politicians to apologise for their actions. There's a great irony in that unionists once criticised republicans for wearing masks at funerals and hiding their identities, but the lack of masks were a major issue at Storey's funeral. Regardless, funerals have always proved crucial to sustaining the republican tradition and the movement did not wish to forego this opportunity.

Dr Maggie Scull is an Adjunct Professor of British and Irish History at Syracuse University London. She is a former Irish Research Council awardee.

The views expressed here are those of the author and do not represent or reflect the views of RTÉ