By TIM BRINKHOF

Many fantasy writers have incorporated the visual footprint of the Third Reich into their fictional worlds. Few, however, have done so as extensively as the creator of Attack on Titan, who revisited this terrible chapter of history not to find inspiration for a fearsome antagonist, but to excavate the divisive ideas that lay buried there.

All living organisms must feed on other living organisms to survive. This disturbing thought, which seems to suggest that the world we live in is an inherently cruel place, dawned on comic book artist Hajime Isayama when he was just a kid growing up in the countryside of Ōita Prefecture, Japan. Unlike so many of the powerful but problematic ideas which cement themselves into the impressionable minds of children, only to be abandoned with advancing age, this one stuck around. Indeed, not only did Isayama refuse to let it go, he even made it the foundation of his very first manga.

Abstract Background by KreativeHexenkueche (Pixabay License /

Inexplicable Origins

Chapter one of Shingeki no Kyojin debuted in Kodansha's Bessatsu Shōnen Magazine on 9 September 2009. Better known around the globe as Attack on Titan (Shingeki no kyojin), it tells of a world in which humanity resides behind a series of three enormous walls that protect it from giant, naked, man-eating humanoids called Titans. One fateful day, when the outermost wall is mysteriously breached and a nearby town is overrun, a boy named Eren Yeager can do nothing but watch as his mother is devoured by one of the invading behemoths.

After joining a sea of refugees past the middle wall, the traumatized youth decides to join the army in order to avenge his mother's death and retake their lost home. On the campaign, he learns that a young man he befriended during military training was responsible for the breach. Bent on killing his former ally, Eren follows him past the walls, where he discovers that the real world is nothing like he ever imagined.

Without any or all prior experience, Isayama had a tough time finding a publisher who would take on his work. Editors across the board were impressed with the originality of his premise, but disheartened by the admittedly rather poor quality of his drawings. Fortunately for Kodansha, their blind faith in then 23-year-old's developing talents ultimately paid off. By 2013, Attack on Titan was selling almost 16 million copies per year, making it the second best-selling manga in the country at the time. That same year, production company WIT Studio released an anime adaptation that, thanks to the leadership of Death Note director Tetsuro Araki and international distributors like Netflix and Crunchyroll, turned into a global pop culture phenomenon – a title which the series has maintained ever since.

Over the years, fans and critics alike have speculated extensively on the possible reasons behind Isayama's explosive and, in many ways, unprecedented success, and the theories they brought forth range widely, from the series having spun a clever twist on the now-oversaturated but onetime feverishly popular dystopian fiction and zombie apocalypse genres, to the artist's supposedly unique ability, according to one sure journalist, to capture "the hopelessness felt by young people" in modern society.

Yet by far the most interesting—and sinister—of these hypotheses, which has only gained in prominence as Attack on Titan approaches its final issue, can be traced back to the very moment of the story's inception. That is, the idea that our world is, fundamentally, cruel.

Yûki Kaji voices Eren Jaeger in Attack on Titan (IMDB)

Alarming Discoveries

In 2015, the Communist Party of China added both the Attack on Titan manga and its anime adaptation to a list of banned foreign entertainment said to "encourage juvenile delinquency, glorify violence and include sexual content." Two years later, the question of censorship spread to the rest of the world with the release of the series' 85th chapter detailing Eren's discovery of Marley, a technologically-advanced nation-state whose sheer existence had been hitherto unknown to the medievalesque society within the walls. Even more shocking was the truth behind the Titans, which turn out to be genetically mutated humans that belong to a race called Eldians who, persecuted by the Marleyan government, are ritualistically turned into cannibalistic monsters and sent towards the walls in order to terrorize the people on the other side.

Interestingly, though, it was not so much these groundbreaking plot twists, but the imagery which Isayama incorporated into his illustrations that proved particularly difficult for western readers to process. Discriminated against for their ability to turn into Titans—an ability that, Isayama tells us, is linked specifically to their ancient and mythological bloodline, and proclaimed by state propaganda to originate from their ancestor having once made a pact with the "devil of all-earth"—the Eldians are separated from ordinary Marlyan society through internment camps reminiscent of Jewish ghettos. They are required by law to wear armbands denoting their race, which are similar in design to the Star of David.

Isayama is, of course, far from unique in this regard. From J.R.R. Tolkien to J.K. Rowling, there are many fantasy writers who have incorporated—or are believed to have incorporated—the visual footprint of the Third Reich into their fictional worlds one way or other. Few, however, have done so as extensively as the creator of Attack on Titan, who revisited this terrible chapter of history not to find inspiration for a fearsome antagonist, but to excavate the divisive ideas that lay buried there. A closer look at Isayama's work reveals that totalitarian sentiment is not only a stylistic influence on his world-building, but an integral part of the story he is trying to tell.

Manga cover art showing Eren facing off against a Titan (Kodansha) (Amazon)

Creating the Perfect Scapegoat

The Titans are not your average monstrosities. Isayama took great care in creating them, and the peculiarities of their design are neither to be understood as trivial, nor as being primarily for the purpose of shock-value, even if their arresting appearance has provoked within readers a morbid fascination that is believed by some to have heavily contributed to the series' rise in popularity.

When they first break through the wall, the Titans appear to Eren—and therefore to us—as the incarnations of absolute evil. Incapable of speech or rational thought, they pursue human beings—which are, by the way, the only organisms in which they express any interest whatsoever—much like animal predators pursue their natural prey, but with much greater fervor and vitality. Unlike animals, however, Titans do not devour human beings for nourishment. Practically immortal and able to regenerate lost limbs—including heads—almost instantly, they seem to be in it solely for the kill. This notion is supported by the fact that many of them sport a frozen, menacing smile. Last but not least, they lack reproductive organs, leaving it unknown—at least at the beginning of the story—how they progenate.

© Hajime Isayama / Kodansha / "ATTACK ON TITAN" Production Committee (IMDB)

The Titans can be seen as a kind of exaggerated version of how people, willingly and unwillingly, visualize the enemy: ethically amoral, physically grotesque, and uncanny in their resemblance to ourselves; human in some ways, bestial in others. Mindlessness, malevolence, indestructability, and infertility—these four characteristics resurface, rather prominently, in the writings of both academics and demagogues, regardless of whether they are left or right-wing. One of fascism's most vocal critics, Winston Churchill, adamantly maintained that totalitarian states thrived on the control of information, and survived only for as long as they prohibited their subjects to think for themselves. During an address delivered to the US Congress in 1938, he argued that what such regimes feared most was not the military might of foreign powers, but the "words and thoughts" of their own people.

To find historical evidence supporting the prime minister's claims, one need only turn to the Reich's Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, which bestowed upon Nazi bureaucrat Joseph Goebbels virtually unlimited authority over the production of art and journalism, thus ensuring that not a single sentence, whether uttered on the stage or printed in a newspaper, contradicted the beliefs of the Führer. Nor was Churchill alone in denouncing the Third Reich as a system based primarily on anti-intellectual coercion. Arguably one of the most memorable representations of the prototypical Nazi soldier and Reich citizen appeared in the 1921 classic film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari under the name Cesare, a mute and mindless slave who—much like Isayama's Titans—had neither the freedom nor the mental capacity to question the murders his autocratic master forced him to commit.

Conrad Veidt in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920) (Photo by Imagno/Getty Images / IMDB)

Although the Titans' lack of reproductive organs can be attributed, rather straightforwardly, to a matter of censorship, it would be unwise to rule out the possibility that this anatomical subtraction was, at least to some extent, a conscious decision on the part of Isayama. German socialist Klaus Theweleit, in a recent study on the fascist imagination called Male Fantasies, discusses at length the conception of the enemy as an impotent creature, one whose inability to give life forces him to take the lives of others instead. Krafft, the masculine hero of Hans Zöberlin's 1937 novel The Command of Conscience (Der Befehl des Gewissens), narrowly avoids a death trap in the shape of an infertile yet libidinous Jewish woman longing to drag the honorable Aryan into the "emptiness, night, and moral solitude" of her existence.

Antisemitism aside, fear of sex and, consequently, sexual desire was by no means unique to Nazi thought, but rather a widely shared sentiment around the globe. Both world wars witnessed whirlwinds of mass-produced and distributed illustrations designed to combat the spread of venereal diseases, with one example of the American persuasion warning soldiers against "booby traps" they may encounter abroad, and another, bent on communication the same message, showing two naked people as their intercourse is interrupted (or prevented) when the female partner's head suddenly transforms into a terrifying, snakelike creature, one whose elongated throat lined with rows of breasts.

The understanding of unrestricted desire as both a self and race-destroying enterprise led the Third Reich to reverse many of the steps taken towards sexual liberation by the Weimer government. It did so, for instance, by the banning and burning of books from sexologists and activists like Magnus Hirschfield and Max Marcuse, as well as by instituting the Nuremberg Laws of 1935, which prohibited mixed marriages and extramarital relations with people of inferior race.

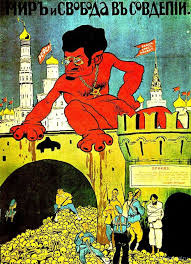

Like Zöberlin's female siren, the male beast became an equally dreaded manifestation of the sex-deprived degenerate. Fear of the "rapacious bestial Jewish male" looking to force himself onto and thus defile "innocent German femininity" grew widespread, thanks to provocative posters showing, among other propagandist scenes, Jewish octopuses latching onto a chaste incarnation of the Aryan motherland—an image which becomes even more striking when considering that Isayama's Titans possess an exclusively male physique, while the three walls that protect Eren's society are personified by and named after three female goddesses: Maria, Rose, and Sina.

The Eternal Struggle

At first glance, Attack on Titan appears to be a variation on the anti-war story, part of a longstanding tradition of pacifist literature that stretches from Walt Disney's 2016 animated feature film Zootopia back to Leo Tolstoy's 1855 Sevastopol Sketches and further, still. Roughly speaking, this type of narrative follows two warring factions which, by recognizing the commonalities between them, come to understand the futility of their struggle and establish peace. When Eren learns the person behind the breach—and the death of his mother—is none other than his best friend, and the mindless Titans he swore to eradicate turn out to be thinking, feeling human beings, the reader is led to believe that the series' true antagonist is not an external entity, but the simplistic, black-and-white worldview that consumes its principal characters.

This revelation is deceivingly foreshadowed in the story's sixth chapter, which follows a ten-year-old Eren as he joins his father Grisha, a doctor, on a visit to one of his patients, a girl named Mikasa who lives in the mountains. Getting to Mikasa's house before his father, Eren finds her parents dead and the girl herself tied up by men looking to sell her into prostitution. Arming himself with a kitchen knife, he manages to outsmart the kidnappers before proceeding to brutally murder every last one of them.

When an understandably horrified Grisha arrives at the scene, he attempts to call upon his son's conscience. But Eren, rather than expressing as much as a smidge of remorse for what he has done, instead becomes enraged at his father's inability to understand what is so perfectly clear to him. "I did not kill people," he asserts (and I'm paraphrasing), "I killed monsters that happened to resemble people."

And yet, even when Eren recognizes that the monsters are people after all, his outlook does not change. On the contrary, the way he sees it, the enemy has not suddenly disappeared, but rather shown its true face. The Marleyans, we are told soon thereafter, have been at war with the Eldians since the dawn of time, a conflict which ended only when the 145 th Eldian king, Karl Fritz, weary of all this bloodshed, took his people to an island on the edge of the world where, after erecting the walls, he used the power of the Titans to wipe their memories.

Fearing the descendants of the royal family might one day change their mind, and desperate to use the king's power for their own good, the Marleyan government eventually sent Zeke Yeager, Eren's half-brother and one of the hundreds of thousands of Eldians left behind on the mainland during Fritz's exodus, to claim the source of this ancient magic. After uncovering the true history of the world, and witnessing the discrimination against the Eldians upon infiltrating Marley, Eren comes to the bleak conclusion that the animosity between the two races will not end until one has effectively annihilated the other.

Those familiar with the writings of Nazi 'crown jurist' Carl Schmitt can see at once that the relationship between the Eldians and the Marleyans is a direct application of his philosophy. In his book, The Concept of the Political, Schmitt identifies what he calls friend-enemy distinctions, antagonisms that run so deep they permeate and override every aspect of life, from social to cultural to economic. According to him, an enemy is not necessarily an enemy because he is ugly or unethical, like a Titan, but because he negates "his opponent's way of life" by virtue of his own, a quality that makes coexistence with the adversary effectively impossible.

When accepting the fact that conflict is an inevitable part of human nature, one is left with two possibilities: surrender and die, or fight and live. In Attack on Titan, these two options are represented respectively by the characters of Zeke and Eren.

Unwilling to kill innocent people, Zeke intends to gain control over the king's abilities and use them to sterilize all members of his race. Once the Eldians will have died out, the world shall be left to the Marleyans, who can thenceforth live on in peace. His "euthanization plan", as Isayama calls it, bears a striking resemblance to the position adopted by Indian pacifist Mahatma Ghandi, who maintained in one interview that the only moral answer to Nazi Germany's Final Solution was for the European Jewry to commit collective suicide.

Eren, using a different moral compass, finds Zeke's plan reprehensible. Recognizing that both the Marleyans and the Eldians essentially fight for the same goal, he sees no evil in fighting fire with fire if it means securing the future of his race. After betraying his brother to come into possession of the king's powers, Eren uses them to create an army of colossal titans with the intention to commit what is more or less the story's equivalent of nuclear holocaust. Convinced that the war will not end until one side has completely annihilated the other, he commands his monsters to destroy all life on earth outside the walls.

(IMDB)

Finding One's Mission

When approaching Attack on Titan, few probably find themselves thinking of Martin Heidegger, yet the man and the manga are connected to each other in interesting ways. As of today, Japan counts no less than six translations of the German philosopher's seminal work, Being and Time—five more than the English language. This bit of trivia is not to imply that Isayama is intimately (if at all) familiar with the work, but it does indicate that Heidegger's ideas, which have an extensive and well-researched relationship with those of Taoism, deeply resonate with Japanese culture.

In the story, various characters use the phrase, "I was born into this world", in order to make sense of their existence, find justification for their actions, and rule out suicide as a solution to their problems. This axiom, the precise meaning of which is as elusive as the writings of Heidegger himself, carries with it a couple of philosophical assumptions that can only be fully comprehended by comparison.

As Heidegger states, Being and Time was first conceived as a critique of traditional ontology—the phenomenological study of being—as it had been practiced in the West for over two centuries. He takes particular issue with the claims of René Descartes, whom he believes presented the world "with its skin off". Denying the famous adage, I think therefore I am, Heidegger argued that an entity could not possibly be understood as independent from the world around them as, by definition, the only way to exist was, simply, in the world. Because the world predates the self, and goes on existing long after the self has dissolved, it also precedes any man-made code of ethics, a supposition which led him to conclude that concepts of good and evil are, fundamentally, dependent on one's place in the world. Consequently, only by accepting one's thrownness, meaning one's artificially determined situation in space and time, could one begin to live authentically.

It should be noted, at this instant, that the scholarship which defends Heidegger from Nazi ideology far outnumbers—and outweighs—the scholarship that hands him over to it. But while the philosopher's ideas provide no direct excuse for violence, some of his writing, notably his Hitler-sponsored 1933 inaugural address, The Self-Assertion of the German University, clearly illustrates how they could be adapted to serve the needs of the Hitlerites. For what is authenticity, except the striving to be true to oneself? And what is true to oneself, except that which one has convinced oneself to be true?

As Eren prepares to destroy the nation of Marley, as well as the innocent civilians he knows reside there, his friends attempt to dissuade him. But Eren, possessed by his fatalistic understanding of reality, refuses to listen, and sums up his argument to them in a single sentence: "I have always been this way." Having grown up in a society that hides behind walls, under the influence of a pacifist king who, unbeknownst to his subjects, wanted them to atone for the sins of their ancestors, Eren resolves to remain true to what he himself has always believed in spite of what others—those whom Heidegger would perhaps refer to as 'the Man', or the 'they-self'—told him: that he will fight for freedom and survival, no matter the cost.

Marina Inoue, Yûki Kaji, and Yui Ishikawa (2013) (IMDB)

Facing the World

Eren's resolution bears, to some extent, a striking similarity to the writings of one of the Columbine killers, Eric Harris, who in his diary wrote that "the human race isn't worth fighting for, only worth killing. Give the Earth back to the animals. They deserve it infinitely more than we do." Perhaps this is what that one journalist meant when they said—in rather vague terms—that Attack on Titan captures "the hopelessness felt by young people in today's society."

But the statements made by Eren and the school shooter, two young and highly motivated perpetrators of mass murder, also vary gravely in that the latter professes mankind to be inherently evil and the world (which, he said, ought to be given back to the animals) inherently good. Eren, believing mankind to be good (that is, fighting for a noble cause), concludes the real enemy to be the world itself.

In that regard, Isayama does not appear to align himself with Adolf Hitler as much as with another influential German figure, Arthur Schopenhauer, who, for his book The World as Will and Representation, wrote the following charming words about a beach in Java covered, "as far as the eye could see", with skeletons,

The skeletons of large turtles, five feet long and three feet broad, and the same height, which come this way out of the sea in order to lay their eggs, and are then attacked by wild dogs, who with their united strength lay them on their backs, strip off their lower armor, that is, the small shell of the stomach, and so devour them alive. But often then a tiger pounces upon the dogs. Now all this misery repeats itself thousands and thousands of times, year out, year in. For this, then, these turtles are born. For whose guilt must they suffer this torment?

The answer is: for none. They must suffer, because they were born into this world.

(© Hajime Isayama / Kodansha / "ATTACK ON TITAN" Production Committee / IMDB)

Works Cited

Ashcraft, Brian. "China Banned Attack on Titan, Death Note, and More." Kotaku. 6 September 2015. Accessed 25 October 2019.

Churchill, Winston. "The Lights Are Going Out". National Churchill Museum. 16 October 1938.

Ehrenburg, Ilya and Konstantin Simonov. In One Newspaper: A Chronicle of Unforgettable Years. Moscow: Sphinx Press, 1985.

Grenier, Richard. "Ghandi's Legacy". The New York Times. 7 August 1983. Accessed 9 March 2020.

Harris, Eric. "Eric Harris's Journal". School Shooters Info. Transcribed and annotated by Peter Langman. Accessed 10 December 2019.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. New York: State University of New York Press, 1962.

Herzog, Dagmar. Sex After Fascism: Memory and Morality in Twentieth Century Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 2007.

hpfan, Vick. "The Influence of Nazi Germany on J.K. Rowling's Harry Potter series". The Leaky Cauldron.org. Accessed 9 March 2020.

Isayama, Hajime. Shingeki no Kyojin. Tokyo, Kodansha, 2009.

Kracauer, Siegfried. From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of German Film. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1947.

"Manga Artist Hajime Isayama Reveals His Inspiration". BBC News. BBC, London. 19 October 2015. Accessed 25 October 2019 via YouTube.

Ohara, Atsuhi, Yamane, Yukiko. "Boosted by anime version, 'Attack on Titan' manga sales top 22 million" (Japan Bullet). Asahi Shimbun. 17 August 2013. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Accessed 1 November 2019.

Orwell, George. "Reflections on Ghandi". Partisan Review, first thus. edition, 1949.

Paskow, Alan. "Heidegger and Nazism". Philosophy East and West. Vol. 41, no. 4, 1991. Accessed 29 November 2019.

Rivera, Joshua. "Teens are absolutely obsessed with this gory series about giant cannibal monsters." Business Insider, 10 Jun 2015. Accessed 9 March 2020.

Rothman, Joshua. "Is Heidegger Contaminated by Nazism?" The New Yorker. 28 April 2014. Accessed 9 March 2020.

Schmitt, Carl. The Concept of the Political. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2007.

Schopenhauer, Arthur. The World as Will and Representation. London: Dover Publications. 1966.

Speelman, Tom. "The Fascist Subtext of Attack on Titan Can't Go Overlooked". Polygon. 18 June 2019. Accessed 2 November 2019.

Szobar, Patricia. "Telling Sexual Stories in the Nazi Courts of Law". Journal of the History of Sexuality. Vol. 11, no. 1/2. 2002. Accessed 2 December 2019.

Super Eyepatch Wolf. "What Makes Attack on Titan So Popular?" YouTube. Uploaded 27 May 2017.

Theweleit, Klaus. Male Fantasies. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1987.

Walter, Damien. "Tolkien's myths are a political fantasy". The Guardian. 12 December 2014. Accessed 9 March 2020.

Zimmerman, Michael E. "Heidegger, Ethics and National Socialism". The Southwestern Journal of Philosophy. Vol. 5, no. 1, 1974. Accessed 23 November 2019.

Zöberlin, Hans. Der Befehl des GewissensBefehl des Gewissens. (The Command of Conscience) Berlin: Zentraverlag der NSDAP. 1938.

RELATED ARTICLES AROUND THE WEB- Attack on Titan 1 (9781612620244): Hajime Isayama ... - Amazon.com ›

- Attack on Titan: Colossal Edition 1 (0884937702974 ... - Amazon.com ›

- Hajime Isayama ›

- Hajime Isayama - IMDb ›

- Hajime Isayama (@hajime_isayama) | Twitter ›

- Hajime Isayama | Attack on Titan Wiki | Fandom ›

- Watch Hajime Isayama draw Levi from Attack on Titan (2017 ... ›

- 14 Things To Know About Attack on Titan Creator Hajime Isayama ... ›

- Manga artist Hajime Isayama reveals his inspiration - BBC News ... ›

- Hajime Isayama - Wikipedia ›