The proposed Acacia Remembrance Sanctuary, masterplanned in 2013 by McGregor Coxall and Chrofi, is a concept for a natural burial and ash interment cemetery in Bringelly, New South Wales.Image: Courtesy McGregor Coxall and Chrofi

David Neustein

The funerary landscapes of Australia were shaped by nineteenth-century ideas transplanted from London, with little innovation in the intervening years. As traditional cemeteries near capacity and the environmental consequences of cremation become apparent, Australia’s funerary industry is in need of more considered solutions for our final resting place.

Pyramid, park and pyre

That we will all die at some point is a given, but what happens after we die is largely a matter of design. The funerary landscapes that we encounter in present-day Australia were shaped by radical decisions made in Victorian-era London, at a time when the architecture of death was comprehensively reimagined by architects, innovators and ideologues.

England’s population more than doubled in size during the Industrial Revolution, growing by nearly nine million people between 1801 and 1850. The unprecedented concentration of people in cities caused an equivalent increase in the numbers of dead. By the early nineteenth century, London’s burial grounds were so overrun that many had swollen metres above the level of the pavement, with human remains strewn about and gravediggers exposed to typhus and smallpox.

In 1824, architect Thomas Willson claimed to have solved this burial crisis with a single big idea. Willson proposed the construction of a Metropolitan Sepulchre on London’s Primrose Hill, with sufficient capacity for some five million dead, equivalent to four times the city’s population. A 460-metre-tall pyramid containing ninety-four floors of catacombs, Willson’s immense edifice would be accessed via steam-powered elevator and provide for forty thousand burials a year over a period of 125 years. The entire megalomaniacal enterprise was devised to be self-funded, with a predicted profit of nearly eleven million pounds.

![The Pyramid to Contain Five Millions of Individuals Designed for the Centre Of The General Cemetry [sic] of the Metropolis (engraving, c1829). This radical concept for a ninety-four-storey cemetery on London’s Primrose Hill was conceived by architect Thomas Willson as a solution to the city’s overcrowded burial grounds.](https://media4.architecturemedia.net/site_media/media/cache/a6/33/a6333409781f4b42eb057a3bd1e6be4a.jpg)

The Pyramid to Contain Five Millions of Individuals Designed for the Centre Of The General Cemetry [sic] of the Metropolis (engraving, c1829). This radical concept for a ninety-four-storey cemetery on London’s Primrose Hill was conceived by architect Thomas Willson as a solution to the city’s overcrowded burial grounds. Image: Collage

Willson’s proposal caught the eye of cemetery entrepreneur George Frederick Carden, who invited the architect to join the committee of his newly formed General Cemetery Company. But Carden sensed that the burial predicament would be solved by building outwards, not upwards. He had glimpsed this future during a visit to Père Lachaise, a new type of grand, monumental cemetery on the outskirts of Paris designed by Alexandre-Théodore Brongniart in accordance with Napoleon’s burial reforms. Carden enlisted Willson to help him emulate Père Lachaise at Kensal Green, the first of seven private garden cemeteries created on London’s periphery between 1832 and 1841.

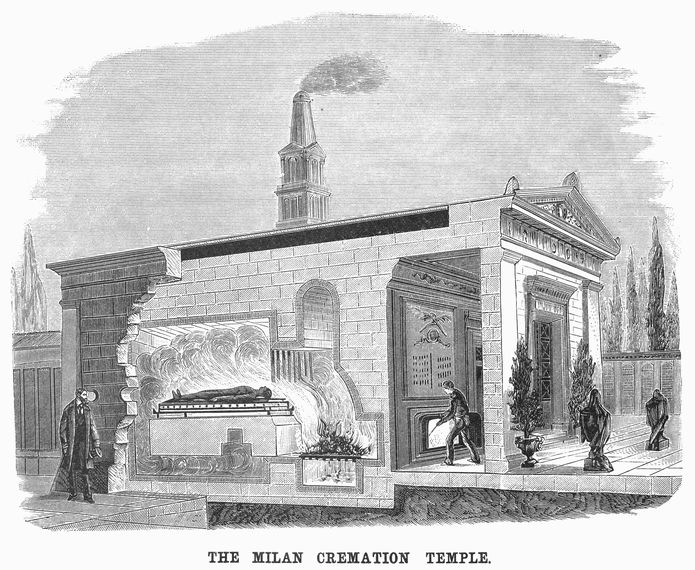

The Magnificent Seven, as these cemeteries came to be known, catered to the tastes of a new middle class and transformed the image of the cemetery in the popular imagination. But the problem of how to bury the great impoverished ranks persisted and the 1848 cholera epidemic that swept through England left a further sixty thousand dead. The implementation of the 1850 Metropolitan Interments Act saw London’s overcrowded urban burial grounds closed and its dead relegated to the city limits. Widespread concerns about burial cost and contamination lingered and, in 1874, Sir Henry Thompson founded London’s Cremation Society to popularize a more cheap and hygienic method for disposing of the dead. Two years later, Europe’s

first modern crematorium – a small gas-fired chamber designed by Carlo Maciachini commenced operation in Milan’s Monumental Cemetery.

An American wood engraving of The Crematorium at Milan, Italy (1881). The crematorium was designed by Carlo Maciachini and opened in 1876. Image: Granger

The Tesco banana

“If only bananas came in some form of natural, biodegradable packaging …” says the caption that accompanies a picture of row upon row of plastic-wrapped Tesco bananas in a popular Twitter meme. Humans, like bananas, come in their own biodegradable container. Just as Tesco adds a layer of wrapping to extend the banana’s shelf life, conventional burial delays decomposition with embalmment, coffins and vaults.

In 1875, the artist and surgeon Sir Francis Seymour Haden published Earth to Earth: A Plea for a Change of System in Our Burial of the Dead. Haden argued for the inherent benefits of natural burial as a rejoinder to Thompson’s burgeoning pro-cremation movement. Cremation only appeared necessary, wrote Haden, because burial practice had deviated so far from common sense. We were meant to be returned to the ground, Haden reasoned, and, if allowed to properly decompose, all London’s present and future dead could be accommodated in just two thousand acres of land.

Haden’s vision was left unrealized. The privatization, commercialization and industrialization of the funerary industry in the decades leading up to his writing had decisively altered the landscape of death. Unlike the garden cemetery, with its grandiose private tombs and crypts, or the crematorium, with ostentatious urns and densely packed columbaria, continual and unadorned burial within a finite patch of earth was a model that offered few products and little profit. Cremation was legalized in the United Kingdom in 1884 and would eventually supplant burial as the prevalent interment method.

The design explores the possibilities of a landscape cemetery, with a site-wide intent to conserve the natural habitat. Off-the-grid facilities include a non-denominational pavilion designed by Chrofi. Image: Courtesy McGregor Coxall and Chrofi

A failure of imagination

The development of the English funerary industry coincided with Australian colonization. But rather than rethink the cemetery paradigm to suit the Antipodes, English settlers simply transplanted the successive archetypes of the Victorian age. Traditional burial grounds installed

at Sydney’s George Street and Brickfield Hill at the turn of the eighteenth century proved inadequate and chaotic, and both were quickly abandoned. A metropolitan-scale necropolis in the picturesque style of Kensal Green was established at Rookwood in 1867, with avenues of imported trees and shrubs replacing native vegetation. Australia’s first crematorium was built in Adelaide in 1903, and Rookwood’s first cremation took place in 1925.

More than fifty years have elapsed since the development of Sydney’s last major cemetery. Australia is currently facing a burial crisis of its own making, with most cities expected to run out of burial space within the next twenty to thirty years. Certain ethnic and religious groups with specific burial requirements, such as Muslims and Jews, are facing much more imminent shortages. But the urgency around our dwindling cemetery space isn’t just about accommodating the segment of society that still adheres to traditional burial rites.

Many Australians now regard cremation as the default option, a logical or even ecological alternative to traditional burial. Cremation accounts for two out of every three Australian interments, with that proportion on the rise. Whereas burial occupies scarce and valuable land, cremation appears to leave little trace. In reality, cremation’s environmental footprint differs dramatically from popular perception: each cremation consumes the equivalent of ten thousand standard light bulbs, forty litres of petrol or a single person’s domestic energy use for an entire month, while releasing harmful gases like mercury and dioxin. In an age of climate change awareness, cremation can no longer be considered a viable option. Other less energy-intensive processes, such as alkaline hydrolysis (also known as water burial, a form of chemical disposal that was used to combat Mad Cow Disease) or promession (freezing and shattering bodies using liquid nitrogen) are not sufficiently tested, socially acceptable or scalable alternatives to burial.

Australia’s burial crisis is more than a failure of foresight, planning or common sense; above all, it is a failure of imagination. Our present-day predicament is due to our collective failure to imagine something more inspiring than tidy rose bushes and close-cropped lawns, countless rows of headstones in polished black or red granite, forlorn little niche walls with letterbox sized holes, expanses of asphalt with sparse clusters of straggled gums, or lichen-covered sandstone monuments listing into the weed-clumped ground. The Australian funerary landscape is uniquely boring, an arid desert devoid of culturally relevant rituals and aesthetically rich experiences. There is little popular or political interest in developing new burial spaces precisely because we have made the cemetery such a lifeless domain.

Designing our end

We are currently witnessing the beginning stages of the earth’s sixth mass extinction. Unlike the previous five, which took place over a span of 450 million years, this latest extinction is caused by humans and was set in motion barely two centuries ago with the English Industrial Revolution. As the consequences of climate change, ocean acidification and species and habitat loss become apparent, the worst-case scenario no longer appears to be the end of civilization but, conversely, that humans will somehow outlive other life forms. In the face of large-scale ecological collapse, humanity must take the chance to gracefully show itself out by minimizing its footprint and ensuring that planetary life survives beyond the present epoch. In this context, the burial crisis can be reframed as an opportunity to make the necessary arrangements for our ultimate end.

Other Architects’ Burial Belt project proposes the reoccupation of cleared and degraded land previously used for livestock for the purpose of natural burial. The price of burial funds the reforestation of the area, repairing the native landscape. Image: Courtesy Other Architects

At Other Architects we are currently developing a project called Burial Belt, which envisions the large-scale transformation of the Australian funerary industry. To be exhibited at the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale, Burial Belt proposes the reoccupation of cleared and degraded grazing land at the city fringe for the purpose of natural burial, replacing carbon-intensive livestock farming with carbon-filtering forest. The price of burial funds the revegetation and reforestation of the surrounding area with indigenous plants and trees, repairing the native environment. Beyond basic costs, individuals can choose to invest as much as they like in this endeavour, potentially greening acres of open space and offsetting lifelong carbon vices. While those buried in this new cemetery will have no lasting monuments or coffins and will decompose into the soil, burial spaces will be provided in perpetuity, providing a covenant over the land that cannot be broken. Eventually, multiple burial sites will join to form a continuous green belt that encompasses the city fringe and constrains suburban sprawl.

Whereas modern cemeteries and crematoria have always been conceived in proximity to urban centres and constrained by problems of capacity, Burial Belt is virtually limitless in scope. One can choose to be buried in the earth of Campbelltown, Crookwell or Cookamidgera, gradually becoming a part of the landscape. The infrastructure required for this burial model is temporary, reusable, lightweight and low-energy, leaving no waste behind. Shedding the artifice of the coffin or crematorium creates avenues for new forms of farewell that are attuned to the landscape and environment, and that acknowledge the fragile and fleeting beauty of the world in which we live. We hope that Burial Belt will demonstrate that while Australian funerary architecture is centuries out of date, we still have time to arrive at a proper conclusion.