By CHRIS BENNETT

One hundred years later, blood still marred the hardwood floor of an upstairs bedroom, indelible testament to a poignant tragedy better suited to Southern Gothic fiction. No matter the scrubbing of a corn shuck mop, or scraping with potash water, the crimson stain held fast to the grain of hand-planed, light-colored pine boards, and clung even tighter to the psyche of an American farming family.

On Nov. 3, 1848, according to hand-me-down narrative, amid the morning commotion of a Georgia family making a final check of fully-loaded wagons bound for the Texas frontier, Jane Story Perryman, 51, slipped down a long hallway splitting four spacious rooms and ascended a back staircase, her heeled steps clicking an acoustic march across a magnificent house empty of its contents for the first time since its construction 15 years prior. She walked into the comfort of her bedroom, a chamber of memories where she might have birthed or nursed a child, and approached the western window, beyond which lay a bucolic masterpiece—a carefully tended flower garden flanked by Talbot County’s low, rolling hills and terraces of partially picked cotton.

Despite the outward appearances of matriarchal success, Jane was a broken woman, facing the loss of family, farm, and community, torn by the prospect of another upheaval and another trip to another frontier to another unknown. No more. Her ties to the land were absolute and her refusal to leave was final. Locked in a battle of wills, she was at the cusp of a decision that would cut her family to the core and leave a scar that could never heal.

Downstairs, her husband, James Perryman, stood by with packed wagons at the ready, anxious to roll toward the future after long months of preparation. Patience thinning as the minutes wore on, and facing the reality of Jane’s refusal to leave, he sent a servant to the upper bedroom with an imperative for his wife—a message insistent on immediate departure to Texas. Seated by the window ledge, Jane stared down into her garden and out across the vista of acreage surrounding the Perryman plantation, and offered a plaintive answer: “My Texas is right here.”

From Jane’s perspective, her response was a line of demarcation—a fait accompli with a single outcome. Remaining in the bedroom, she likely reached beneath a multi-layered dress and slid a pistol from the garment’s fabric folds, fingering the trigger—one pull from the afterlife.

Staring at the second story of the house—coaxing, pleading, imploring, hoping, demanding—James waited in vain for his wife’s appearance as the servant exited the front door and delivered confirmation of Jane’s decline, magnifying the strain of an awkward stalemate. Moments later, the report of a single gunshot tore apart the tension of the Perryman house, the sound instantly magnified across bare floors and walls, ultimately reaching the ears of a stunned husband. Mortally wounded, Jane collapsed onto the pine boards of the bedroom floor, the lead bullet delivered by her own hand.

In bitter irony, James shelved his westward aspirations, unloaded the wagons, and remained in Georgia for the rest of his life. He buried Jane in the peace of her beloved flower garden and covered the plot with a marble slab, just 50’ below the second story bedroom window. Significantly, her gravesite was solitary—no other relatives ever had been, or would be, buried in the garden, or on the greater 350-acre property. Jane was left to sleep in isolation.

The forlorn narrative surrounding Jane’s death is stirring—but is it correct? Enter the mystery.

A Telltale Obituary

History is often captured in blurred snapshots, and Jane’s lachrymose final days and months elicit more questions than answers. Yet, the turmoil speaks to circumstances more than common in farming, pioneering and landholding families of the day. Jane’s apparent death by her own hand marked the end of a life, the end of a family structure, and the beginning of a time-shrouded enigma pitting oral tradition against the veracity of a telltale obituary.

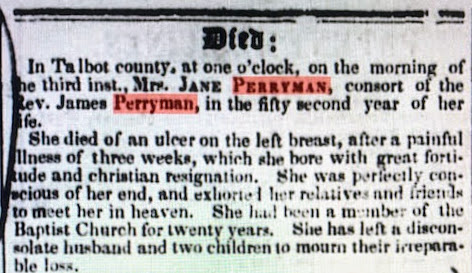

Eleven days after Jane’s passing, in seeming contradiction to the suicide account, the Perryman family placed an opaque obituary in a Nov. 14, 1848, newspaper, attributing blame for Jane’s demise on “an ulcer of the left breast.” The mystery of her death, punctuated by the obituary, and contrasted by a similarly hazy grave slab inscription, leaves absolute conclusions as to Jane’s fate in the eye of the beholder.

The strange disparity requires a trip back in time in order to hear the faint whispers of Jane’s voice, and to peek behind the curtain into history’s seldom seen side of agriculture and family dynamics. Truly, in many ways, spilled blood never dries.

The Ghost House

Just off a two-lane highway in Georgia’s west central Talbot County, Dan Akin and Robert Wright are searching for Jane’s forgotten grave. Born in 1965, Akin is a gumshoe historian with a wealth of knowledge about forgotten figures in Talbot and Harris counties. In addition, he is a distant nephew of Jane Story Perryman, and his great-great-grandfather, Henry Allen Story, was Jane’s half-brother.

Wright is a maverick explorer and creator of Sidestep Adventures, a riveting YouTube channel chronicling cemeteries, old homes, artifacts, farmland, and all points lost in the cracks of time. Intent on locating and documenting historical sites, Wright uncovers a steady stream of graves and homesteads near the brink of oblivion, often navigating in the deepest scrub of the Peach State.

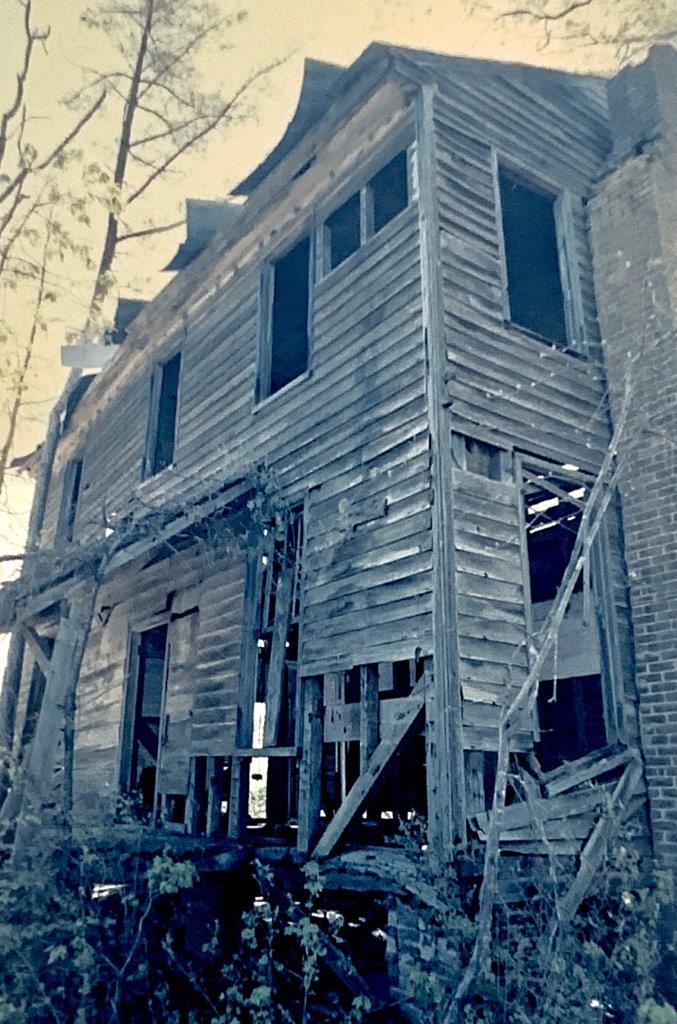

However, on a hot June afternoon in a woolly thicket of woods, walking sticks in hand in case of timber rattler encounters, Akin and Wright cannot find their bearings. Time has swallowed the Perryman house. As the pair moves through the decayed remains of the site, the present has overwhelmed the past. Simply, the structure is gone.

“This was the ghost house when I was a boy, because Miss Jane stayed after everyone else left,” Akin explains. “Time moved on and now nobody seems to know she’s even here. It’s almost like she became invisible.”

“The house and land that Miss Jane so desperately didn’t want to leave is now in ruins and overgrown,” Wright echoes. “To think if she could get up and look around now. The view out the bedroom window of this house, her last living view, has drastically changed.”

As late as the mid-1980s, the house still stood, although the dwelling was in its death throes, a wooden skeleton picked apart as carrion for scavengers: “The last time I went near it was when the timber was harvested on the place around 1982,” Akin recalls. “Someone had removed all the flooring from the first and second floors, then using a chainsaw, had cut and taken away all the floors joists. It was a fragile shell with no support and later collapsed in the wind.”

Emerging from a tangle of periwinkle vines and avoiding the spiny points of Hawthorn trees, Akin takes note of strewn chimney bricks and nubs of field stone that once served as foundation pillars, but sees no sign of Jane’s grave in the copious undergrowth. He walks west, poking and prodding into the foliage for several minutes, until his foot accidentally strikes the hard edge of the inscribed marble slab.

“I can’t help but wonder why she did it,” Akin reflects, “but I know you don’t cast blame into the past when you just don’t know enough details, and you don’t judge history. Sometimes you just let the story tell itself.”

A Bitter Drama

In 1797, Jane was born into the Story clan, one of the largest landholding families in the Warren County region, in eastern Georgia. She was one of the oldest of 25 children fathered by Samuel Story (1776-1838) throughout two marriages to Winney Brooks (1772-1811) and Stacy Duckworth (1795-1860).

Samuel came from meager origins, but ascended agrarian society in bootstrap fashion, accumulating ground acre by acre, clearing land, acquiring slaves, and building up a large cotton plantation. However, with 25 children in contention, land didn’t go far as inheritance, and each child also was gifted livestock as they came of age.

In 1816, Jane married James Cobb Perryman (1795-1864), also of Warren County, the son of a Baptist minister, Elisha Perryman. The couple had four children: Eliza Anne (1819-1873), Anthony Griffin (1818-1869), James Griffin, and William Julian. When western Georgia opened to settlement in 1825, following the Treaty of Indian Springs and the ceding to the state of remaining Creek Indian ground between the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers, a lottery divided the land into plots typically amounting to several hundred acres. James moved his wife and growing family to what was frontier country, purchasing Talbot County land from a lottery winner in 1827, in order to clear timber and start a plantation.

For Jane, raised in the comforts of fine society, a stone’s throw from Augusta, the overland switch from east to west represented vastly more than a change in 150 miles of geography. In a sense, the move was a permanent departure from all things familiar—a traumatic life change. “Miss Jane knew she was leaving everything behind for good, and going as a pioneer to a densely wooded, foreign place, with almost no ties to friends and neighbors,” Akins says. “Imagine leaving behind a family with sufficient money and all the accoutrements of polite society and imported goods, and jamming everything you own into a few wagons. Literally, the Talbot County area was a rough place where if you didn’t make what you needed by hand, you often couldn’t get it.”

Following the same calling as his father, James was a man of the cloth, intent on seeding churches among the tiny settlements popping up in western Georgia. Yet, in the age, a minister often made a pittance in salary, or essentially was unpaid, leading to the necessity of bivocational employment. Translated: James farmed in order to preach. “He wasn’t a huge farmer,” Akins says, “but the Census of 1850 shows he owned 15 slaves. Take into account that his farming neighbors owned 50, 60 or 100 slaves, so that gives an idea of his farm size. Basically, he farmed as a means of livelihood to enable his ministry.”

In the early 1830s, 4 miles west of Talbotton, the county seat, James built Jane the “Perryman House” on the family plantation composed of approximately 350 acres. Two stories, the house was finished with hand-planed, unfinished, grooved Georgia pine boards covering 10’-high ceilings (8”), floors (8”), and walls (10-12”), adorned with wainscoting and crown molding, along with multiple finely crafted fireplace mantles.

Roughly 3,000 square feet in area, the house’s basic configuration was two rooms down and two rooms up, with two large shed rooms at the back. Into the front door, a hall ran to rear, separating the downstairs rooms (17 x 17 square) and shed rooms. In addition, a dogtrot led to a detached kitchen behind the main house. Up the back staircase, another hall cut across the second floor, with spacious rooms on either side, including Jane’s bedroom. The home property included numerous dependencies—barns, slave quarters, smokehouses, seed storage, and feed cribs.

The Perryman house became a locus of family and financial success: crops raised, children reared, and grandchildren spoiled. At first blush, the home was a tapestry of halcyon success, Akin explains, but inside, a bitter drama was unfolding.

Blessed are the Dead

Standing over Jane’s grave after clearing away debris and growth, Akin and Wright find a 3’x5’ slab turned on its face and broken into several parts, possibly a result of damage from past logging activity. Flipping over the marble segments and piecing together the puzzle, the ornate inscription is akin to a time machine: “Sacred to the Memory of Mrs. Jane (Perryman); Consort of James Perryman and daughter of Samuel & Winney Story; Born May 11, 1797; Married Feb. 11, 1816; Joined the Baptist Church Feb. 19, 1829, & Died Nov 3, 1848. Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord.”

Plain in description, the epitaph arguably is notable for its exclusions: No terms of endearment, and no mention of motherhood or children. Granted, the omissions may be incidental, but considering the circumstances of Jane’s purported suicide and her segregated burial, the absences may be key clues.

Brother Perryman

As a boy in Talbot County, and in conjunction with his status as a relative, Akin heard the account of Jane’s suicide on a steady loop from family members, farmers, and neighbors within close proximity to the Perryman plantation. One of Akin’s favorite haunts, and a repository of oral tradition, was a general store roughly a quarter mile from Jane’s grave. On countless afternoons, Akin would pull open the store’s screen door, walk into a time capsule, and grab a chair or pull up a piece of floor, intent on listening to the banter of owner Frank Lucas, along with old-timers Gene Culpepper and Jim Alex Bussey. The men were farmers, born and raised within close proximity to the Perryman place, with grandparents living at the time of Jane’s death.

Born in 1903, Lucas repeatedly detailed witnessing bloodstains in Jane’s bedroom, according to Akin. “Mr. Frank told me many, many times that’d he’d personally seen the blood on the floor, still visible upstairs after the house stood vacant over 100 year later,” Akin recalls. “I listened to Mr. Frank tell the whole story so many, many times. And Mr. Gene and Mr. Jim Alex, they knew I was related and they all told of the exact same events about ‘Brother Perryman,’ the preacher, and Miss Jane.”

Possibly, James’ off-farm role as “Brother Perryman” became the touch paper, legitimate or otherwise, for a marital impasse, and Jane’s alleged self-slaughter in 1848. At a minimum, his dual vocation must have at least been an influencing factor, according to Akin. James had a direct hand in starting churches across Talbot County and its conjoining counties, and he was consistently in demand as a revival speaker. As western Georgia was settled, the 1840s became a decade of steady movement even further west, on through Alabama and Mississippi, eventually into Texas.

Texas had gained statehood in 1845, and was a source of opportunity, cheap land—and church building. “James had already helped establish numerous small country churches, so it stands to reason that he wanted to do the same in the newest frontier. I was always told that he felt like he was supposed to go there and spread the gospel,” Akin explains. “Out of the blue, James came home one day and told Jane something like, ‘We’re moving to Texas.’ I can only speculate, but it looks to have been more than she could handle. Just like she later said, ‘My Texas is right here.’”

Right or Wrong

In 1848, Texas was emerging from the Mexican-American War (1846-1848). Depending on James’ chosen destination, the trip could take 1,000-plus miles across Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana, requiring months of overland travel either solo or in a convoy. The newspapers of the day flashed stories—headlines Jane would have read and heard—of Indian wars and settler massacres, child abductions by Comanche tribes, and the general wilds of the Texas frontier. At a minimum, she knew the reputation of Texas’ frontier as unbridled country, and was keenly aware of the basics and hardship of a potential move west.

Did Jane react to James’ instruction with abject dread? Did she immediately buck his plans? Whether or not she died with those details, a modicum of presumption allows for a basic assessment, even from a perspective 170 years after the fact: Jane had worked almost 20 years to establish a prosperous farm, and watch her children grow into adulthood, marry, and have their own children. Decades earlier, she had already sacrificed, rode away from a family of plenty and fine society, and carved out life in the dense woods in the tough west of her native state. With Texas on the horizon, she again faced the prospect of pulling up stakes, leaving family, friends, church and familiarity, all in exchange for an even rawer frontier. It’s not a stretch to posit that Jane may have decided she would not, and could not, go through with another move.

Yet, the mores of the era dictated a wife’s general acquiescence to a husband’s instruction—at least in public. Jane was bereft of parental support or guidance, her father dying a decade earlier in 1838, and her mother gone since 1811. From a conjectural standpoint, even Jane’s maiden family may have bowed to convention and backed James’ decision; i.e., once the die was cast, debate was futile, leaving Jane in emotional isolation. “God only knows now what thoughts were in Jane's mind,” Akin says, “but right or wrong, she probably was privately telling James that under no circumstances would she ever leave the home that he had so meticulously built for her.”

Into Eternity

Texas in his crosshairs, James needed at least months to communicate by post with friends, colleagues or contacts in order to set up a travel plan, and shutter his Talbot County operation. Further, he needed a sizable chunk of time to get his affairs in order, nail down a destination, and frame the logistics. Whether months or far longer, the prolonged preparation time for a journey to Texas is germane to Jane’s state of mind, because over an extended period of reckoning, she might have felt the weight of increasing anxiety as each detail dropped into place, as if watching grains of sand draining inevitably from an hourglass.

Coincidentally, a female neighbor of Jane’s committed suicide a decade prior, Akin explains. Henry L. Benning’s (Benning later became a Confederate general; Fort Benning is his namesake) parents lived 7 miles from the Perryman house. “Anna Benning, who was General Benning’s sister, killed herself about 10 years before Jane’s suicide. I don’t know the reasons, but it’s a curious footnote, and Jane would have certainly known Anna, and she would have also known the circumstances.”

Regardless of what Jane knew when, and what influences pushed her to a state of desperation, the morning of Nov. 3, 1848, found her beyond a cry for help or delay tactics, and there was no theater or histrionics recorded prior to her seclusion in the bedroom, Akin notes. Alone, beside her window, in her house, and on her land, Jane fired a single bullet into her body and was hurtled into eternity.

Or did she? A look at oral tradition versus obituary throws both light and shadow on the odd circumstances of Jane’s death.

A Most Curious Obituary

“After Jane’s suicide, James unloaded the wagons and canceled the trip. In some ways, that’s the saddest part of the whole story,” Akin says. “After all the plans to move halfway across the country, he stays in the house where she killed herself, and buries her right outside the window.”

There were burial options in close proximity—community and church cemeteries inside a mere quarter mile distance—but Jane was buried within feet of the spot where she died. Was her grave location in the garden at her request, or a result of James’ remorse, or was it tucked away on the family property, forever alone, due to a sense of shame? “We’ll never know,” Akin says, “but stories like this were covered up by families, especially in this age. People were ashamed. The farming community was so close-knit and its members were often related, so everyone knew each other’s business. They farmed together, worshipped together, and were neighbors. Those same neighbors, and not the direct families, were usually the ones that passed down unmentionable stories.”

On Nov. 14, 1848, 11 days after Jane’s death, the Perryman family placed an obituary in the Columbus Enquirer newspaper, lamenting the passage of mother and wife. “Died: In Talbot County, at one o’clock, on the morning of the third inst. (present month), Mrs. Jane Perryman, consort of the Rev. James Perryman, in the fifty second year of her life. She died of an ulcer on the left breast, after a painful illness of three weeks, which she bore with great fortitude and Christian resignation. She was perfectly conscious of her end, and exhorted her relatives and friends to meet her in heaven. She had been a member of the Baptist Church for twenty years. She has left a disconsolate husband and two children to mourn their irreparable loss.”

Among several details, the obituary draws attention to Jane’s “left breast,” and assures readers that she was “perfectly conscious of her end.” As opposed to the tepid inscription on Jane’s privately viewed and isolated grave inscription, the publicly viewed obituary is effusive in comparison. (Once again, the slab inscription on Jane’s solitary gravesite: “Sacred to the Memory of Mrs. Jane (Perryman); Consort of James Perryman and daughter of Samuel & Winney Story; Born May 11, 1797; Married Feb. 11, 1816; Joined the Baptist Church Feb. 19, 1829, & Died Nov 3, 1848. Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord.”) Bluntly stated, Akin sees significant contrast in the tone of the private versus public final messages of remembrance.

The obituary, Akin contends, was a polite cover-up. The real truth, he adds, was an open secret: “I believe Jane shot herself in the left breast...and the family wound up telling the public that she died of an ulcer,” he explains. “The neighbors knew well what happened. Mr. Frank Lucas' grandfather, Marshall Lucas, was born in 1829, and died in 1923, when Mr. Frank was 20 years old. Mr. Frank quoted his grandfather almost daily on various subjects. Mr. Gene Culpepper's Harris relatives intermarried with the Perrymans. The Bussey family had always lived nearby. Mr. Frank's wife, Virginia, told me that her family, the O'Neals, always told her the same story. They all knew what had occurred.”

The Lone Constant

James remained on the Perryman place for several years after Jane’s death, and according to the Census of 1850, he still lived in the house, along with a daughter, Eliza, and a son-in-law. The census listed James as a minister—not a farmer. By the Census of 1860, James had departed from the Perryman place and resided in Buena Vista, Ga. (Marion County), assuming the pastoral role at the local Baptist church. He remarried and started more congregations in Marion, Stewart, and several other counties. In 1864, one year prior to the close of the Civil War, James, 69, passed away, and was buried in Buena Vista, according to Akin, approximately 30 miles south of Jane.

The Perryman home and farm remained in the family for at least five generations. During the 1920s and 1930s, the land was planted into peach production, but eventually evolved into timberland. Jane’s home, ever more neglected, transitioned into a tenant house, and was vacant by the 1950s. Essentially, every aspect of the plantation changed and every actor on the stage changed—except Jane. Her grave was the lone constant.

Left Behind

Walking out of the woods and scrub after recording the grave’s location and condition, Akin and Wright once again leave Jane Story Perryman in isolation. “I’m 55, and as a child, everyone in my area knew about Miss Jane’s resting place,” Akin laments. “Just decades later, her grave is ceded to the woods and elements, and she’s on the verge of complete disappearance. She got left behind, and now nobody seems to know or care that she’s here.”

“The whole story of Miss Jane is so very sad,” Wright adds. “From her suicide, her final act, to staying in that house and on that land that she obviously so dearly loved—so much so that the thought of leaving the house and land may have literally killed her.”

Jane’s life was paved over by history’s march, a common occurrence when the perception of dishonor and shame cloud a memory. However, her death speaks volumes about deep attachments to land, community and family—sentiments that spark anguish when a heart is separated from its moorings.

“It’s an awful, awful tale that just overflows with anguish,” Akin continues. “Who was the victim? Jane? James? Both of them? Their family? You can’t judge when you don’t know what was going through their minds, but you can sure feel so many levels of pain.”

“I think the whole account makes us all ask questions about ourselves,” Akin concludes. “One thing for sure: Once you hear this story, you can’t stop thinking about Miss Jane.”

Indeed. Jane is the invisible woman, forever a ghost in the garden, haunting the memory of a house she never left.