Swapnil Dhruv Bose·

“It is obvious that art cannot teach anyone anything, since in four thousand years humanity has learnt nothing at all.” – Andrei Tarkovsky

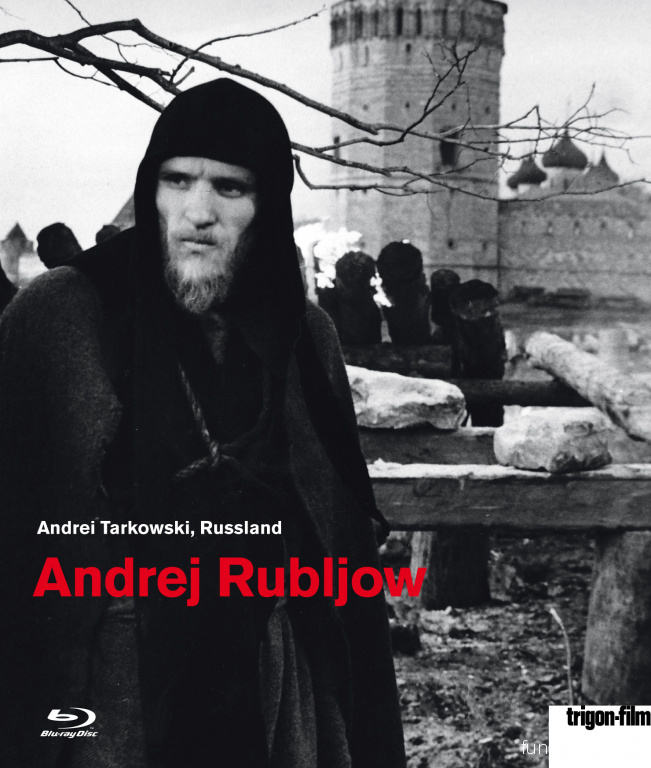

Andrei Rublev was Andrei Tarkovsky’s second feature after his stunning 1962 debut Ivan’s Childhood, a project which solidified the belief that the burgeoning filmmaker was capable of great things, despite being initially banned, censored and dismissed by the Soviet regime for its “ideological erroneousness”. It has been 55 years since Tarkovsky’s masterpiece first came out and, in that time, it has been recognised as one of the essential works of Soviet cinema which explores the omnipresent questions of art and faith. Although I still believe that Stalker, released in 1979, was his magnum opus, Andrei Rublev is crucial for a better understanding of Tarkovsky.

Set in the volatile medieval period of 15th century Russia, the film is loosely based on the life of the legendary painter Andrei Rublev (Anatoly Solonitsyn) but is more of a document of the brutality of the times that preceded the Tsardom of Russia. Through the ascetic figure of Rublev, Tarkovsky reflects upon the role of the artist in a world where moral systems do not exist anymore. Separated into eight distinct chapters (along with a prologue and an epilogue), Andrei Rublev is a cinematic novel which transcends the limitations of a literary text by subjecting the viewer to a more intense experience that is simultaneously cerebral and visceral. The prologue begins with a scene that appears to be completely disconnected from the rest of the narrative. It depicts Rublev’s world from the perspective of a man who has attained the ability to fly with the help of a hot-air balloon, a new Icarus whose wings are made of primitive technology. He ultimately crashes to the ground, setting the tone for what’s about to come. For the next three hours, Tarkovsky relentlessly pursues the same philosophical statement: man has been left floundering on the floor because of the hubris of his belief in an anthropocentric universe.

We track the evolution of Rublev as he embarks on a spiritual journey that eventually leaves him speechless, unable to muster up the courage to utter a single word. There is a distinct divide between the members of the Eastern Orthodox Church who claim to know what’s best for the people and the peasants who cannot see past the suffering of their own lives. Many of them have lost faith, choosing to adopt a life of hedonistic pleasure in order to numb the pain of their tragic existence. This separation creates a constant conflict within Rublev who cannot comprehend that the things he considers to be “sinful” are actually liberating for others. In a fantastic debate with his mentor Theophanes the Greek, Rublev’s hope for humanity is countered by Theophanes who harbours a more cynical view of human civilisation. He asks Rublev to entertain the possibility that the idea of evil is not just a localised demon but a fundamental attribute that is present in every single individual. During this debate, we see a reenactment of Christ’s crucifixion as we are told that Christ would be crucified again if he came back to this world:

“Judas sold Christ. And who bought him?”

The pacing of Andrei Rublev is deliberately slow, like most of Tarkovsky’s works, a decision which force us to stop and think about the images that are presented to us instead of mindlessly consuming them as we are often programmed to do. In an interview, Tarkovsky explained, “[Andrei Rublev] is shot in very long takes, to avoid any feeling of artificial, special rhythm, in order that the rhythm should be that of life itself.” This enables the viewers to immerse themselves in the stages of disillusionment that Rublev goes through. He is violated by a group of hedonists who believe in free love and grows afraid of painting something that will scare people. It is almost as if Tarkovsky is channelling semi-autobiographical confessions through the mouth of Rublev, expressing his doubts and fears of his responsibility as an artist. How can an artist avoid the destruction of his faith if the truth itself is blasphemous?

Irma Raush as Durochka. (Credit: Film still / Columbia Pictures)

In what is probably the most striking section of the film, Rublev witnesses an apocalyptic collapse of all human ideals. Rublev believed that “brotherly love” was the highest form of connection but he sees a brother turning on a brother when the younger brother of the Grand Prince attacks the city of Vladimir with an army of Tatars. Widespread violence binds the bleak landscape together as marauders kill and burn without any hesitation. Even God fails to hinder them. They break into a cathedral and slaughter the people hiding in the protection of their supposed saviour. This becomes a transformative experience for Rublev who ends up killing a man in order to save a woman from getting raped. The camera captures his dizzying anguish as he speaks to a hallucinatory vision of the dead Theophanes, vowing to never speak again and admitting his failure as an artist who cannot communicate to his people.

Rublev loses his faith in men but still believes in God, convinced that the world he lives in has turned its back on the true essence of life. However, the final chapter serves as a reaffirmation and resurrection of the old Rublev. Tarkovsky tells the story of Boriska, the son of a bellmaker who scams his way into becoming the leader of a project involving the construction of a bronze bell for a church. He tells them that he is the only one who knows the secrets of his father’s trade but is shocked when he somehow manages to fulfil his objective. In Eastern Orthodoxy, the chiming of the bell suggests the restoration of the belief in God and the reconciliation of humans with the divine. When Rublev sees Boriska lying on the ground and crying in disbelief, he breaks his vow of silence to console him and promises to create art again. It is unclear whether this act of God made Rublev believe again or whether it was the flaws of man that taught him how to truly empathise with the lost souls around him.

Andrei Rublev’s epilogue is the only part of the film that is in colour. The camera pans over the beautiful paintings of Rublev, obsessing over tiny details and letting the audience come to their own conclusions. Underlined by an overwhelming sense of sadness and grief, we can almost observe Rublev’s anguish seeping out of his depictions of divinity.