Marc Swanson Draws Comfort From Rural Cemeteries and '80s Club Music - The New York Times

Fire and Ice: Marc Swanson at Mass MoCA and Thomas Cole National Historic Site

By Jackson Davidow

View of "A Memorial to Ice at the Dead Deer Disco," 2022–23, at MASS MoCA.PHOTO TONY LUONG

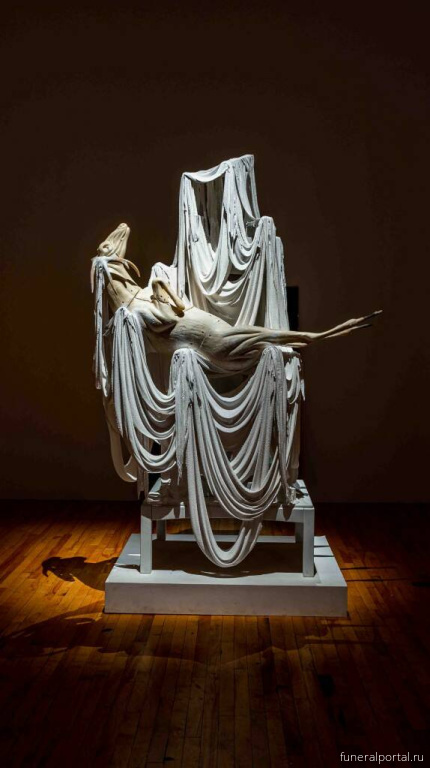

At Mass MoCA in North Adams, Massachusetts, two cavernous dim galleries are strewn with dozens of eerie assemblages that conjure a wonderland of death. Composed of plaster, wood, fabric, and prefabricated objects, the predominantly white sculptural works in Marc Swanson’s exhibition “A Memorial to Ice at the Dead Deer Disco” draw on a limited lexicon of household items and architectural features—framed photographs, tables, stairs, drapes, mirrors, and lighting fixtures—juxtaposed with elements invoking nature and the outdoors, from deer dummies to branches, rocks, and icicles.

As if exploring a haunted house, viewers wander through the shadowy galleries, catching sight of a pietà featuring a Grim Reaper cradling a deer, a platform for a go-go dancer embellished with fabrics draped from branches, and a hanging, gently rotating chain clustered with shimmering antlers. The works all riff on each other yet are unique, and seem curiously in a state of deterioration, despite the material excess. Assortments of photographs recur throughout the show, set in the kind of utilitarian metal frame found in any middle-class living room or positioned in rhinestone-studded wall mosaics; they present generic scenes of nature (wintry waterfalls, moonlit skies, a ray of light bursting through a forest), historical snapshots of queer people partying, and some recognizable pop-cultural imagery such as Bruce Byron as the motorcycle hunk in Kenneth Anger’s film Scorpio Rising (1963). A few video works contributing additional natural imagery are embedded in the sculptures and reliefs.

These melodramatic works make up Swanson’s most monumental exhibition to date. They combine the kitsch visual culture of post-Stonewall queer nightlife and domestic spaces with the aesthetic languages of 19th-century landscape painting. The latter two categories are more dynamically intertwined in a contemporaneous installation Swanson mounted at the home, studio, and yard of the Thomas Cole National Historic Site, a 90-minute drive away in Catskill, New York. Like Swanson’s artworks on display in North Adams, the items that queerly intervened in the quaint house-museum of Cole, founder of the Hudson River School and a noted environmentalist, included a busy collage involving tassels, two bejeweled deer, a vitrine filled with framed photographs, a lifeless bouquet, and electric candles.

The works’ installation at the house-museum initiated a dialogue between Swanson and Cole: In one instance, a Swanson sculpture of three interlaced deer necks and heads evoked a knotty tree with three trunks in Cole’s painting Hunters in a Landscape (1824–25), which was also on display. For the painter, as the label explained, this trunk speaks to the striking peculiarities of trees untouched by human settlers, who sought to control their growth so that there is less variation—a sentiment that likely resonated for Swanson with his interest in identifying queer images of, and situations in, nature. Despite their differences in era and chosen mediums, Swanson and Cole are linked by a romanticist appreciation of the natural world, a propensity for the grandiose, and an exploration of the interplay between the formulaic and the distinctive.

View of “A Memorial to Ice at the Dead Deer Disco,” 2022, at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site.©PETER AARON/OTTO

Swanson’s larger project is framed as a meditation on the climate crisis by way of a reckoning with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. As the wall text emphasizes, the countryside affords Swanson now what the urban gay disco did back in the 1990s: a space of freedom and belonging, yet one at risk of extinction. Thus propelled by alarm at the prospect of future loss, Swanson casts his assemblages as memento mori. At Mass MoCA, on one icicle-covered sculpture resembling a signpost with an illuminated frame bears a portrait of Harold, the caustic character from Mart Crowley’s play-turned-film The Boys in the Band (1968/1970). Premiering less than a year before the Stonewall riots, the drama was groundbreaking for its frank depiction of gay intimacies, both loving and toxic. The actor who played Harold, Leonard Frey, died of AIDS-related complications in 1988 at age 49.

View of “A Memorial to Ice at the Dead Deer Disco,” 2022–23, at MASS MoCA.PHOTO TONY LUONG

But what do Frey and other queer ghosts here have to do with climate change? Describing the show’s inspiration in an interview in BOMB earlier this year, Swanson recounted, “I began to conflate the AIDS crisis and climate change, because the climate crisis was giving me déjà vu of the AIDS crisis.” While the artist is right that similarities exist between the two global catastrophes—chiefly, inadequate governmental action, as he notes, as well as the rampant corporate profiteering across both histories—this conflation has the potential to be dangerous. The AIDS epidemic is far from over, and those who suffer the consequences of these crisises differ, as well as the reasons for leaders’ inaction. Though Swanson’s installations are provocative and at times magnificent, this mishmash of queer historical memory is ill-suited to addressing something as immense and complex as climate crisis. Swanson himself may experience a similar sense of loss from both, but to mourn them in the same prophetic, sentimental, and scarcely political gesture is to elide their nuanced conditions, and to detract from the artwork itself.