By Holly Harris

Glenn Gould’s closest confidantes talk about their memories, and what lessons we might learn from his life in the post-COVID-19 world.

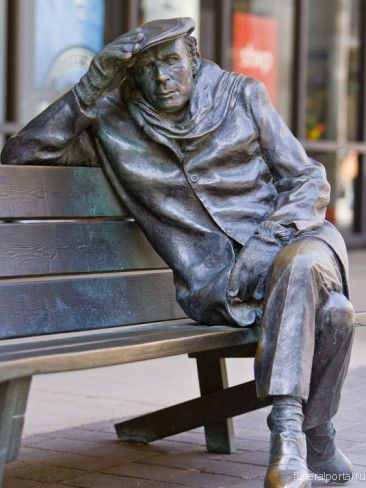

On the threshold of what would have been Glenn Gould’s 88th birthday (coincidentally, also the same number of keys on the piano), the legendary Canadian pianist’s legacy has continued to fascinate, enthrall, and inspire the classical music world.

New generations of listeners discover more than his imaginative world infused by J. S. Bach’s polyphonic works. They find Gould’s commentary, and not least of all, his wry wit that became more zany with each passing year since his shocking death at age 50 on October 4, 1982.

But, he has never really left us.

Even now, nearly 90 years after his birth on September 25, 1932, Gould still possesses an uncanny ability to remain ahead of the curve.

He might also now be hailed a musician for our times in a brave new COVID-19 world, as well as pioneering architect for ideals of social/physical distancing, as manifested through his equally fabled eccentricities. “In some ways,” wrote Edward Rothstein upon Gould’s death, “his entire life was an experiment in esthetic isolation.”

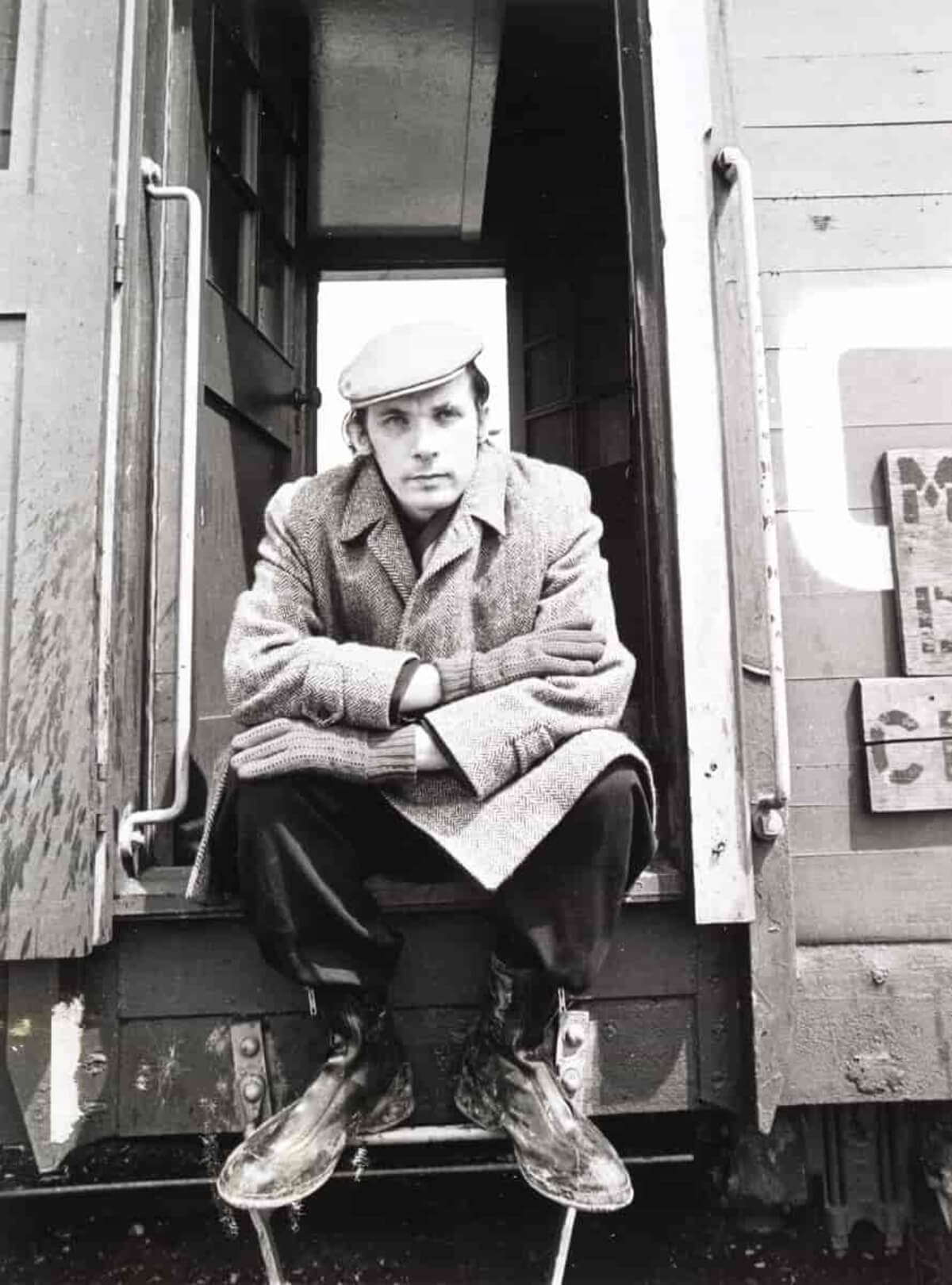

A few of those eccentricities include being a notorious germophobe — the pianist abhorring to shake hands with others while preferring to make social contact through hours-long, late night telephone calls. Swaddled in an overcoat, scarf and gloves in the middle of summer, singing and humming during his playing, and perhaps most overtly, abandoning the live concert stage for the womb-like security of the recording studio, he delivered his final concert performance on April 10, 1964 at Los Angeles’ Wilshire Ebell Theatre.

Even his stable of riotous alter egos — Sir Nigel Twitt-Thornwaite, Dr. Karlheinz Klopweisser and Myron Chianti — might arguably be viewed as an ultimate act of psychic/social distancing. By removing his own persona from the equation, Gould thus became free to express different ideas and perspectives through alternative voices than his own — the ultimate stepping back, or distancing, from his own carefully crafted image, and wholly authentic self.

But even art that imitates life is rarely by design, and it’s far too simplistic to assume that such a fiercely complex maverick like Glenn Gould would fit neatly into some contemporary, even formulaic tenet.

Those who were closest to Gould throughout his career were given a rare, front row seat to his life and art, intimate friends and acquaintances, musical collaborators, writers, editors, biographers and fiercely loyal guardians of his legacy for posterity.

May their contrapuntal voices weave together in this journalistic fugue in the key of Gould, evoking perhaps his boundary-pushing contrapuntal radio documentary, The Idea of North, as each seeks to articulate, illuminate and ultimately celebrate the reclusive — and still elusive — artist.

Ray Roberts (Photo: Faye Perkins)

A Trusted Personal Assistant Sets The Record Straight

Paradox.” That’s what Ray Roberts replies over the telephone from his Pickering, Ontario home when asked to describe his friend, the late, great Glenn Gould.

“He had sort of this split personality. There was this persona figure that he presented to the world as ‘Glenn Gould,’ complete with all these idiosyncrasies, but in many ways, he was just a regular guy,” he explains, describing his own relationship with the artist as, “very straight-up.”

Now 81-years-old, Roberts speaks matter-of-factly of his dozen years spent at Gould’s side as his personal assistant — or self-described “glorified gofer” -— driven to share his personal anecdotes and stories for the annals of time. He speaks freely of his friend —nothing is off limits during our interview — while clearly stating his desire to get the record straight once and for all, to counter persisting swirls of inaccuracies and misconceptions about the artist. Though Gould may be long gone, his faithful assistant remains fiercely loyal to the end, as a trusted, trustworthy friend.

Roberts first met Gould circa 1970, then working as a sales representative for Coca Cola. He was invited by the pianist’s long time recording engineer Lorne Tulk to help set up recording equipment in the old Eaton Auditorium located in downtown Toronto, where Gould regularly recorded after growing resistant to travelling to New York City’s Columbia Records (later morphed into CBS Records).

Some of his gofer duties included keeping Gould well stocked with his adored Arrowroot cookies, fielding a myriad of telephone calls and inquiries from around the world, as well as chatting regularly with Gould during his own daily telephone calls to Roberts that arrived like clockwork at 11 a.m., 2 p.m. and 11 p.m., in which the pianist would share his thoughts, plan ahead, and dissect the day, with Roberts serving as an attentive, critical, sympathetic sounding board.

He offers his own theory on why he was able to maintain a particularly close relationship with the exceedingly private artist, when countless others who had longed for greater connection and even intimacy with Gould all too often fell by the wayside.

“Frankly, Glenn was very good to me, and helped me in a lot of different ways. I was grateful to him but never felt he owed me anything,” Roberts says candidly. “That became the secret, and he understood that I was not a threat. Glenn could let me go at any time, but of course, that never happened.”

Like most human relationships, he readily admits that theirs was not always smooth sailing, including several arguments that grew “testy”, and even once getting fired — albeit briefly — while en route in Gould’s massive Lincoln to NYC, after Roberts defended the pianist’s father Russell Herbert for wishing to remarry following the death of Gould’s beloved mother Florence in 1975. Other topics were off-limits, or even taboo during their conversations:

“I never dared to talk to him about his interpretation of music or anything like that; however, if we were talking about something else that he didn’t agree with, we could go on for three hours if you didn’t watch it,” he reveals.

“But Glenn certainly listened to my opinion on a lot of things, and would either accept them, or debate them as with anyone else. He was also very involved with news of my family and kids, and came up to my house several times as he also did with Lorne.”

In fact, so trusted was Roberts that he was presented with a treasure trove of priceless memorabilia and artifacts, including “around 800” recorded tapes of Gould’s piano performances, and multiple studio gizmos and gear to store in his basement, now in the process of being carefully sorted, documented, and preserved as historic Gould archives through US-based company Primary Wave Music Publishing, which acquired Gould’s music rights in August 2017.

It was also Roberts who received the chilling phone call at 3:30 p.m. from the pianist two days after the world celebrated Gould’s 50th birthday on September 25, 1982, marked hand-in-hand with the eagerly anticipated new CBS Masterworks release of Bach’s Goldberg Variations. After Gould ominously confided that he felt “unwell,” Roberts immediately whisked him from his residence at the now demolished Toronto hotel Inn on the Park to Toronto General Hospital, where he was diagnosed with having suffered a severe stroke.

Gould slipped into a coma on Thursday, with Roberts still clearly affected 38 years later and growing emotional when recounting how he struggled to comfort an increasingly agitated, frightened Gould during his daily hospital visits. He also notes the overwhelming responsibility of fielding panicked, stunned calls from around the globe that fell on his shoulders during that week, and after news broke of Gould’s death on October 4.

“He had sort of this split personality. There was this persona figure that he presented to the world as ‘Glenn Gould,’ complete with all these idiosyncrasies, but in many ways, he was just a regular guy.”

“That was a horrendous week, and the world just exploded,” he says in hushed tones. “But Glenn was my friend, and there wasn’t anything that I wouldn’t have done for him. It was my job and I always said, all along, that whatever he wants, I’ll try and do it as best I can.”

Roberts grows thoughtful when asked how the artist, who eschewed cooking or going out for meals, and typically ordered room service, including his daily “scrambles,” a.k.a. scrambled eggs — and “sometimes veal” — might have fared during a pandemic. The reclusive artist is also well known for his love of driving well into the wee hours through the streets of Toronto, often accompanied by Roberts, as well as venturing further afield on Highway 400 to break proverbial bread with truck drivers and factory workers at local diners.

“He would go to these places where nobody knew him from Adam. He listened to the conversation and loved it because no one was bothering him,” Roberts says. “Glenn was always very connected to the world around him, and worried about people, and particularly ‘small’ people. A woman from Saskatchewan once wrote him a letter saying, ‘Your music helps get me through the dreaded winters, and makes my life complete.’ Glenn treasured that, as doing something that caused some good in the world was very, very important to him.”

He also freely admits that Gould avoided crowds, and making any form of physical contact with others like the plague, while generally despising audiences, once colourfully referring to them as a “force of evil,” “chilling,” and even exemplifying a “rule of mob love” during a 1966 interview with Canadian-American television personality Alex Trebek that ultimately drove his decision to leave the concert stage behind forever at age 32.

“In many ways, Glenn was just a normal guy, but he operated at a genius level, too, with so many complexities and contradictions,” Roberts says frankly — there’s that paradox again. “Glenn would certainly embrace today’s live streaming of concerts and I’m sure it’s something he would really have taken to heart.”

When asked what he’d like the world to know most about Gould, Roberts doesn’t miss a beat.

“That he was a caring person. He wasn’t some kind of iconic robot out there, but cared deeply about people and particularly ‘small’ people,” he says. “I’m indebted to him because I did things that many, many people would never get an opportunity to do. I felt very protective of him as that came with the territory, but he was always ‘just Glenn’ to me. He was my friend.”

A Great Pianist With A Humble Ambition

It’s no secret Glenn Gould is now hailed as one of the greatest pianists of the 20th-century — if not for all time — taking his rightful place beside other such legends as Horowitz, Ashkenazy, Rubinstein and Rachmaninov, among others.

However, Lorne Tulk, Gould’s primary audio engineer and close friend since the mid-1960s, who also notably edited the 1982 Goldberg Variations, shares another perspective:

“Glenn had only one ambition in life, and that was to be a good person. And that is from his lips, not mine,” the former CBC technician says over the telephone from his north Toronto home. “Being a moral person of great honour and integrity was extremely important to him,” he further underscores his point about the artist who famously referred to himself as “the last Puritan.”

Tulk first met a then 18-year-old Gould — poetically — on Christmas Eve 1950, entering his life as a precocious, deeply curious 10-year-old who cut an acetate record of the artist’s inaugural CBC Radio national broadcast through a live feed from his radio technician father’s downtown Toronto recording studio. After the performance, Gould stopped by Tulk’s household to pick up the recording, becoming instantly gobsmacked that a young child had just recorded his debut radio broadcast.

“We sat together in our living room and Glenn wanted to know how I knew how to do this. We got into a very lengthy conversation, which developed into a much stronger relationship later,” Tulk shares of that night.

It would take another 17 years before their paths crossed again in 1967, when Tulk was hired to work on Gould’s first radio documentary, The Search for Petula Clark, a humourous take on the British pop star who fascinated Gould to no end, and later, Gould’s iconic The Idea of North in 1967. His first installment of the CBC-produced Solitude Trilogy, among others, was also created with Tulk’s expertise. A trusted and skillful collaborator, Tulk also worked extensively with Gould during the series of piano performances he recorded at the Eaton Auditorium.

Now both adults, their first formal project together proved that Tulk’s like-minded, simpatico sensibility aligned squarely with Gould’s restless creative vision, further deepening their friendship. So close Gould felt to his engineer, that he wished to make their relationship official, suggesting they head down to Toronto City Hall so that he could legally adopt Tulk as his brother.

“He used to ask me quite frequently, ‘Would that be possible?’ ‘Would I object?’” Tulk recalls. “He was desperate to make it legal and was really serious about it. But when I told him I already have three brothers and a sister, and they might have something to say about that, he simply said, ‘That’s so dear,’ and never asked me again.”

There were other barometers of their close-knit bond. Gould wanted Tulk to have a key to his apartment at Inn at the Park — with the latter refusing the gesture saying he didn’t want “that kind of responsibility”— and shared his actual birth date, then unknown to the public, and not publicly on record in a pre-Google age. Tulk kept it a closely guarded secret all those years while Gould was alive, ever loyal and respectful of the artist’s desires.

Gould also presented him with a gift of one of his famous, low-slung piano chairs, which he has to this day as a treasured reminder of their decades long friendship, after returning it to Gould during a brief spat, and ultimately returned to him by Roberts following the artist’s death. Incidentally, Ludwig Van did an entire podcast about Gould’s Chair that you can listen to here.

Like Roberts, Tulk also received regular late night phone calls (“his phone was his personal company” he says), and often rode with the artist in one of his luxury cars, including his Lincoln. Gould also stopped by nearly every day at Tulk’s home, which he shared with his late wife and two children, to visit, debrief, and discuss news of the day.

“The fact of the matter was that Glenn was always isolated,” he says. “He lived alone but he wasn’t a lonely person. He loved it, and enjoyed his own company, and got along with himself very well. He was isolated, but never, never lonely,” he states.

He also attests to Gould’s astonishing photographic memory — the pianist could learn an entire work by memory with just one reading — while affirming that the pianist never played with a score during recording sessions. He customarily would leave his music behind in the sound booth for technicians to refer to and fix hiccups with every painstaking, intensely laborious, analogue tape splice.

“Glenn had only one ambition in life, and that was to be a good person. And that is from his lips, not mine.”

“Glenn had such an unbelievably curious mind. He was also quite an avid reader, and read at least two books a week, not counting four or five newspapers each day. He remembered everything,” he says. “He was without question the most intelligent human being I’ve ever met, and I’ve met a lot of really intelligent people. But Glenn was in a class by himself.”

For the record, that insatiable appetite for facts and figures also translated to the stock market. Gould’s keenly analytical mind ability to pull out polyphonic threads in Baroque tapestries of sound also led to his making a killing trading stocks. “I remember him saying to me at one point, ‘I’ve got to give up this piano as I’m making a whole lot more money on the stock market,’” Roberts remembers.

More than anyone, Tulk is uniquely equipped to speak to Gould’s deep love affair with the recording studio, dispelling the popular belief that the artist withdrew from public performances to become more reclusive. Recording fired up his creative juices and fed his creative appetite for daring innovation, including making his radio documentaries.

“Gould gave up the professional stage to be on the electronic stage. He enjoyed recording because he could play what he wanted to, and in the way that he wanted,” Tulk affirms. “He hated giving concerts, and once told me was bored to tears playing the same things, day after day in different places. He really didn’t care for that kind of life, and also the competitive nature of audiences.”

But he also refutes another long held Gouldism, i.e. the artist’s disdain for shaking hands with others, potentially fraught with transmitting germs and viruses.

“It wasn’t for protection, but more about his gentle nature. He would tell people that he just met, ‘I shake hands very, very softly, and very gently,’ as he didn’t like having a firm handshake where somebody squeezes the life out of you,” Tulk explains. “It was more about his personality and his humanitarian side that wouldn’t even kill a fly, or an ant on the sidewalk. He would walk out onstage and be looking down to make sure there wasn’t some insect that he might be stepping on,” he adds of the also equally known animal lover. Half of Gould’s estate went to the Toronto Humane Society, with the other half allocated for the Salvation Army.

Asked what kind of advice Gould might give to those living during an age of COVID-19, Tulk reflects for a moment before offering his reply.

“First of all, he probably wouldn’t give you advice, but if he did give you anything, he would say, ‘Be you,’” he states. “There was this American poet named Chip Young who came up to live in Toronto. Glenn also met him and we became very close friends. Chip wrote a little poem that went something like, ‘I can be me. That’s all I can be. And you can be you, because that’s all you can do, is be you. So I will be me, and you will be you.’ Glenn loved that poem because that was exactly his philosophy on life, and what he lived by,” he says.

“Solitude was very comfortable for Glenn, and it’s where he did his best thinking, including getting in his car and driving up to Wawa where he would stay in the hotel with the goose on top,” he explains. “But he also had a deep love for people and genuinely loved life, be it animal or mineral or vegetable. He was very folksy, and very friendly. If he met you tomorrow, he would love to have a conversation with you, and see how you live your life, or find out what’s interesting to you. He would be completely wrapped up in that and furthermore, would remember it,” Tulk says of his friend.

“When Glenn embraced something, he totally embraced it. And life was the biggest embrace of all.”

Musical Collaboration

World-renowned Canadian clarinettist James Campbell is among a rarefied group of musicians that performed with Gould as a chamber player. He remembers the sheer impact of meeting the legendary artist for his first time as a 23-year old student, just returned home to Toronto from his studies with acclaimed clarinettist Yona Ettlinger in Paris, and invited by late CBC producer and director Mario Prizek to play with Gould.

“I walked in and saw this vision,” Campbell reveals during a telephone interview, still with palpable wonder at entering Toronto’s CBC television studios for their first rehearsal of Debussy’s Premiere Rhapsody For Clarinet and Piano, a charming yet notoriously difficult competition solo commissioned by the Paris Conservatoire and written near the end of the composer’s life in 1910.

“Gould was there and he had on big rubber boots and an overcoat, plus a hat and scarf, and was playing Schoenberg. He looked like this apparition with a single light over the piano in this large space, and I didn’t know what to do, as I was just a kid,” the clarinettist says. “I watched him for a while, wondering what to do, but when he knew I was there, he came out of his intense focus and was so nice, telling jokes; very, very pleasant and very welcoming. He immediately assumed I was playing by memory, and I thought, ‘well, now I do,’” Campbell adds with a chuckle.

He shares another detail that provides insight into Gould as a musical collaborator. “Glenn didn’t want the fans on from the cameras, and it must have been about 35 degrees in the studio. Gould would sing during his playing and the producer would stop and tell him he was singing again. Glenn would be so apologetic,” he shares. “He was very kind, and very nice; seemingly open to ideas but his musical personality would pull you in, and inspire you to join him.”

The two artists proved so in tune with each other that their inaugural encounter subsequently led to five more performances together, including works by Schoenberg and Walton.

Notably, it also led to Gould asking Campbell to be his clarinettist for his “little studio orchestra with people that he liked,” intended to explore music that caught Gould’s fancy and for which he planned to lead as its conductor following his 50th birthday — his “next act,” and latest dream project as also confided to Tulk shortly before his unexpected death. He had informed his audio engineer that he wished to leave the piano behind for good, and “change careers,” although obviously still in music. Campbell still deeply regrets the lost opportunity to this day, with its many imponderable, and impossible what-ifs.

“Glenn was easy to work with but also demanding. He would never tell you what to do, but asked me what I wanted. In his mind we were colleagues,” he says of being given a rare opportunity to be inside Gould’s creative process. “He was not the ‘great Gould’ telling us what he wants, and that’s why I was so excited to be a part of his conducting projects. I was very sorry he died before they came about, as I had been really looking forward to that and seeing what he was going to do next.”

“I remember realizing that I was the only one in the world at that moment hearing Glenn Gould live, and I was just a metre away.”

Campbell — who also never shook hands with the pianist, and was another recipient of Gould’s late night phone calls, as well as regularly getting a lift home with the artist after their evening rehearsals — affirms that Gould, born prior to an age in which CDs revolutionized the music industry, would have eagerly embraced today’s 21st century digital technologies. “He loved all the controls in the recording studio and would have enjoyed it immensely,” he says.

Every since Geoffrey Payzant’s ground-breaking Glenn Gould: Music and Mind first appeared in 1978 — notably the sole biography published during Gould’s lifetime and the only monograph for a decade, and unique at the time for taking a deep dive into the pianist’s philosophies and approaches to music-making — there have been ongoing debates and discussions about Gould’s ideal of musical “ecstasy.” According to Payzant, the pianist himself describes this lofty state in his telecast, The Age of Ecstasy as, “a delicate thread binding together music, performance, performer and listener in a web of shared awareness of innerness.”

Campbell grows thoughtful when asked if he feels Gould lived more in a state of solitude or isolation — the latter buzzword now so firmly etched into today’s collective psyche and an integral part of the COVID-19 lexicon, and aligned with Rothstein’s perspective in his journalistic benediction of 1982.

“Glenn was always very aware of everything. He wasn’t just in his little cocoon but knew exactly what was going on at all times,” he says, before adding a third option, based on his decades of critically acclaimed performances lauded around the globe evoking that “powerful magic,” as described by Payzant in which performer and listeners merge as one.

“When you’re performing onstage, and if you’re lucky, you’re able to reach a state of ecstasy and that’s what hooks performers. Maybe it’s only for 20 seconds, but it’s something that you never forget and it’s what you strive for,” he explains.

“I remember when I was rehearsing alone with Glenn and he asked to listen to a piece he had been practicing that was about 15 minutes long. He was completely in this other world, and was performing as strongly, and intensely as ever you see on the stage or screen — he was full on. He had entered this space of great focus and communion with music, which is a form of ecstasy too,” Campbell says. “I remember realizing that I was the only one in the world at that moment hearing Glenn Gould live, and I was just a meter away. I remember telling myself, ‘Jim, remember this moment.’ It is a memory that is always inspiring to me,” he says.

“Glenn had an incredible ability to transcend whatever was going on around him and I don’t quite know how he did that, but it was very special and I feel very fortunate I was able to witness that. Glenn didn’t need an audience to reach that state, he just did it.”

A Crazy Interview Leads To Friendship

Pulitzer Prize winning music critic and author Tim Page, who notably edited the first collection of Gould’s writings, The Glenn Gould Reader in 1984, and is regarded as one of the world’s leading Gould experts, recalls his initial encounter with the pianist as a fledgling arts journalist, then writing a cover story on Gould for now defunct, New York City weekly arts magazine, the SoHo News in October 1980. Their two-hour telephone interview led to an intimate friendship, conducted mostly through numerous late-night telephone conversations in which they spoke of music, Gould’s deep love for Canada, including his views on the idea of North, politics and other topical matters of the day.

It also led to Gould inviting Page to join in his aptly titled Glenn Gould Discusses His Performances of the Goldberg Variations with Tim Page, a meticulously scripted interview prepared by Gould, in which a character “Tim Page” queried “Glenn Gould” about his two performances of Bach’s masterful work in 1955 and 1982.

“He was friendly, he was interesting. He was courteous, and he was funny during our two years spent over the phone,” Page reveals from his NYC residence — the same apartment where he first interviewed Gould from his living room couch 40 years ago.

Page describes boarding a train from NYC to Toronto back in August 1982, notably two short months before Gould’s death that fall. The then 27-year old was paid a princely sum of $75 for his participation in what he wryly calls “this crazy interview,” originally intended to be recorded at Gould’s studio at Inn at the Park, but ultimately taped at an alternative downtown Toronto locale due to unexpected circumstances. The interview, akin to a radio drama, provides a rare glimpse into Gould’s own thoughts and feelings about the keyboard work, and with every seemingly off-the-cuff comment carefully crafted, and ultimately included on a three-CD set A State of Wonder: The Complete Goldberg Variations 1955 & 1981 released by Sony Classical in 2002.

Page is also among an elite few for another reason, further underscoring the mutual, instinctive trust immediately apparent during their first and only in-person meeting that summer.

“When I arrived at his studio, Glenn put out his hand, which I was not expecting. And I took it very, very gently and shook it as gently as I could,” the writer recounts of making rare physical contact with the notorious germophobe — and briefly holding the fingers that had brought to brilliant life so many of Bach’s glorious works.

“He was very shy, and his eyes never met mine for an hour or two. But then we spent two days talking about the interview, as well as a lot of time laughing and watching films, and just chatting about subjects that we really wanted to discuss,” Page reveals of those two intensive days of preparation.

“He was pretty much the guy I had expected, except he looked in terrible health,” he admits. “His hair was very, very thin and he was absolutely pale. He was paunchy. He didn’t look like a well man, but the spirit was there. The brain was there, and the friendliness was there.”

As with Campbell, Page was also treated to a rare solo performance. The interview went on till 6 a.m. At that point Gould went to the studio piano and started to play.

“I got to hear Glenn play a few of these variations live, which was amazing, and even though I was practically dead from exhaustion, kept telling myself, ‘you idiot, wake up, Glenn Gould is playing the piano for me,’” he says. “I kept pinching myself so I could stay awake. It was probably about a 15-minute little concert which I’ve never forgotten to this day.”

Their bond went even deeper than friendly, musical camaraderie.

Both shared a form of autism spectrum disorder known as Asperger’s Syndrome, with Page receiving a diagnosis later in life at age 45, as documented in his bestselling 2009 memoir Parallel Play, and Gould now widely accepted to have suffered from the same, albeit little-known and understood back then condition — also substantiated by both Roberts and Tulk during our interviews.

“We were two intensely autistic people who were nevertheless high functioning, and had the same obsessions,” Page shares candidly, describing Gould as a “kindred spirit.” One of those obsessions in the writer’s case proved to be his prodigious gifts as a filmmaker, including notably making over 30 films by the tender age of 13, as well as appearing as the youthful subject in documentary A Day with Timmy Page.

“We would talk about film, we would talk about book and politics. We spoke about what was going on in the world, and of his great love for Canada,” he says. “Both of us had spectacular memories, and were intensely involved with dates, so would talk about ‘this is the anniversary of this or that.’ We would go on forever.”

Another common bond proved to be an aversion to drawing close to others throughout their lives, as well as experiencing deeply felt existential states of loneliness. However Page states that one upside of autism is being able to do “spectacular things” derived largely from an innate, “curious intensity,” such as making films, writing books or playing piano like a blazing banshee. “We really are different, some of us,” he says simply, before sharing another heartwarming story of their close, natural bond.

Gould once wrote his friend one of his deliciously witty, tongue-in-cheek songs, including poking fun at Page’s enduring love for minimalist music, intending to sing it to him over the telephone. The critic still regrets answering the call directly rather than having it recorded on his answering machine; becoming even more of a lost opportunity after his the pianist promised to record the song for him later — and tragically died before that could happen.

“He was friendly, he was interesting. He was courteous, and he was funny during our two years spent over the phone.”

When asked how Gould might have fared during a global pandemic, as a pioneer and even trailblazer for these unparalleled times, Page shares his perspective.

“I think Glenn would have loved the Internet. He would have been able to make several recordings of all the pieces he loved and share different versions for those who wanted to hear them at different speeds. He was a germophobe and didn’t like much physical contact. But he would have enjoyed things like Skype and Facebook and the way it let him keep in touch with people from far away but still enjoy his friendships while keeping his distance,” he says of his friend.

As years continue to fly by, it’s both deeply humbling and profoundly poignant to realize that many of those who knew Gould, best, including his own family members, and lifelong as well as newer friends and colleagues have since passed on. Most recently, Gould’s devoted piano tuner of 40 years, Verne Edquist died peacefully at age 89 after a long illness on August 27th.

Page pays special tribute to Roberts, whom he says, “guards the secrets still,” and praises him for his “wonderful, noble devotion” in unwaveringly protecting Gould throughout his lifetime.

“Ray knew Glenn better than anybody else on the planet. There aren’t many people I admire more than I do Ray,” he says. “It was his job to take care of Glenn when he was alive, and it’s still his job now. He’ll always take it seriously.”

Page, who first met the pianist in his late-20s and is now in his mid-60s, is also keenly aware of being part of an exclusive club with an ever-dwindling membership as a torchbearer and personal witness to Gould’s legacy and genius, and in good company with Roberts, Tulk, and Campbell.

“Most of Glenn’s friends were a lot older than I am, so I’m used to being the one who can really talk about him now,” Page points out. “There aren’t that many people I can talk about Glenn with now, because most people didn’t know him other than through his recordings and writings. I’m not exactly a kid either now, so I always enjoy sharing these stories whenever I can,” he says, before adding a final grace note to this fugue of overlapping, entwined voices in the key of Gould.

“We were a charmed circle,” he says. “Glenn loved us for whatever reason, and we loved him back.”

#LUDWIGVAN

Get the daily arts news straight to your inbox.

Sign up for the Ludwig van Daily — classical music and opera in five minutes or less HERE.

![]()

Glenn Gould: A State of Wonder - The Complete Goldberg Variations 1955 & 1981

https://www.amazon.com/Glenn-Gould-Complete-Goldberg-Variations/dp/B00006FI7C