News

written by Alex Gallacher

We heard the very sad news that Robin Morton died suddenly on 1st October. Our thoughts and condolences are with his partner Alison and their family.

I don’t use the term ‘legend’ lightly when talking of Robin Morton for he was exactly that. His contribution to traditional music was both important and pioneering and was driven by a deep passion and respect for the music. We featured an interview with Robin in 2016 which focussed on his early years leading into the 1960s and the folk revival. Ewan MacGregor who worked with Robin at Temple Records conducted the interview – the same studio at which Robin engineered Dick Gaughan’s landmark album Handful of Earth, released in 1981 on Topic Records. Ewan’s introduction to that interview lined up some of those other landmarks that Robin became best known for as well as the genuine heartfelt dedication he had for traditional music:

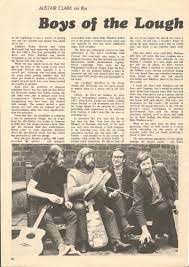

“For decades, Robin Morton has made a massive contribution to traditional music. As a founder member and player-manager of the early Boys of the Lough, he helped take traditional music to huge audiences worldwide. As a long-term manager, producer and ‘fifth member’ of Battlefield Band, one of the great institutions of Scottish traditional music, he has brought talent to the fore for decades. He is an enthusiast, author, song-collector and promoter of folk music, who was instrumental in founding the Ulster Folk Music Society and served as Edinburgh Folk Festival director, with a stint as chairman of the Scottish Record Industry Association. His record production has won acclaim time and again over the decades, and his Temple Records label has championed Scottish music since 1978. He pioneered early releases of harp music and Gaelic song, long before they fell into popular favour; releasing records of Alison Kinnaird, Flora MacNeil and Christine Primrose when no other labels would do so.”

It was at the Ulster Folk Music Society that he was introduced to a young Fermanagh flute and whistle player called Cathal McConnell who later, along with Robin and Tommy Gunn, another Fermangah musician and ‘a great fiddle player and carrier of tunes’, would form a trio which they named after a reel they played: Boys of the Lough.

Below, is Ewan’s interview with Robin in full that was published on Folk Radio in 2016…I can think of no better way than celebrating Robin than sharing in his own words those magical years.

Your path into traditional music was not one driven by your family or upbringing; you were in fact a Jazz fan, although it’s easy to forget that Jazz, blues and folk often shared the same bill during the 60s. How did your own personal shift from jazz to folk happen?

Well, I grew up in Portadown, Northern Ireland, and didn’t hear very much traditional music, if at all, in the forties and fifties when I was young. My father was interested in Jazz and introduced me to people like Bunny Berigan, Red Nichols, Miff Mole, Kid Ory and Louis Armstrong, although I sort of discovered Louis myself. I actually thought for a while that I must obviously be related to Jelly Roll Morton in some way and was very proud of that. Then I was seriously pissed off when I found out that he wasn’t really called Morton – he’d changed his name from Ferdinand Joseph LaMothe! I think this was possibly so his family wasn’t associated with his career – though I never did find out why he chose Morton.

I was always interested in authentic music though, so for jazz I really wanted to hear music from New Orleans. As I got a bit older I would go up to a record shop in Belfast, run by a guy called Solly Lipsitz who ran a jazz band that played Chicago style music. Solly was a big influence in Belfast. His shop was the only place you could get jazz records in Belfast at that time and I would travel home with my ’78s under my arm; I think the first one I bought was Jelly Roll Morton playing ‘Dr Jazz’. Solly used to get the American sailors to bring records over with them, then he would buy them and sell them on to us; the adoring public – there were quite a few of us at that point. I found out much later on, having read about Van Morrison and then talked to him about it, that he did the same thing and used to go into Solly’s shop to buy his ’78s.

Were you playing also music at this point, as well as listening?

I started to try to play the cornet, in my bedroom playing it against the wall. I just wanted to be Louis Armstrong. I never did learn to read music properly but I listened a lot and played along with records and could actually do a right good job of the ‘Heebie Jeebie Blues’ solo. When I say a ‘right good job’, I could sort of make my way through it at least! I wanted authentic music, I really did. But in Portadown there was nobody else to play that music with. Then the skiffle thing came along, and I started to listen to that. Again, I found myself moving towards what I saw as the ‘authentic’ skiffle, if you like. Ken Colyer had an authentic skiffle band around and I listened to them in preference to Lonnie Donegan. Although when you listened to Lonnie Donegan you got interested in Lead Belly and moved through to the blues, then to old-timey and Appalachian music where you began to hear folk songs. Then you begin to realise that a lot of those folk songs came from Ireland and Scotland mainly and also quite a few from England, because at that time there really was a strong living tradition there.

After I left school, I taught mentally handicapped children, and I went to Manchester for a year to train. This would have been around 1959. I bought my first guitar in Manchester – in Johnny Roadhouse’s Music shop. Johnny Roadhouse was a great sax player who had this famous shop as well. I also started to go to all-night jazz sessions at the left-wing coffee bar (my political views were beginning to show at that point) and heard great players like Ronny Scott, Tubby Hayes and the Jazz Couriers. Also I went to a few folk sessions. Blues and folk clubs were beginning to develop then, and I heard and became quite friendly with the Liverpool Spinners, and started to sing a few of those songs.

I remember being very strongly influenced by the weekly Hootenanny Show on TV, recorded in Edinburgh, which introduced me to new music. People from my generation will remember that show. It was a really excellent program; everybody who was anybody was on there, people like Martin Carthy, Cyril Tawney and Nadia Cattouse. I remember seeing Archie and Ray Fisher, who were great. I started to listen to Robin Hall and Jimmie MacGregor and to sing some of their songs, a lot of which came from Ireland. At that time there was also folk music on the six o’clock news if you can believe that; they had a magazine programme which would feature music. So there was a kind of revival going on and I got involved. By the time I came home from Manchester, in 1960, I could play the guitar a bit and sing a few songs. I suppose at that point I was singing Ewan McColl songs, as everybody was.

So how did you become interested in ‘collecting’ and recording folk songs yourself?

Well when I got back home it turned out that in fact my family did have some interest in traditional music, I just didn’t know it. My mother’s family were all farmers and my uncle Tom McCreery, a man I became very close to, looked after the family farm. Tom loved singing and knew a lot of songs, although he didn’t sing himself, and he would get me and his son to sing. It was him who suggested going to a great pub called The Head O the Road, where they had singing every Saturday night, to sing a few songs. I ended up getting really involved at this pub. It was about ten miles outside Portadown in a townland called Tartaraghan, and it was owned by the Lawsons, I believe it still is. I went out there and sang one or two songs, Ewan MacColl songs maybe or something like that, and these men who were singing Victorian ballads and vaudeville songs and so on, all of a sudden they started to sing traditional songs. So I knew that were more songs out there, and I wanted to find them.

Actually, the first folk songs I recorded as a field collector were, believe it or not when I was in the hospital. I’d been playing rugby for Portadown – not very well, third team or something – and I’d had a kicking playing in a match in Dungannon, Co Tyrone. So I was in the hospital there for about ten days with a back injury – I could hardly move. Dungannon is a real country town, lots of farming folk. I got talking to the other patients on the ward, and the craic was mighty. I had previously bought a little Philips tape recorder (1 and 7/8 inches per second recording speed – really high quality!) to rehearse on. When we started to talk about songs, one of my fellow patients, a man called Frank Mills sang me a song called ‘Roll Me From The Wall‘ and I recorded him on my little machine while I was flat on my back.

Another patient, an old man who was lying opposite me in the ward, wanted to sing as well but he wouldn’t sing directly into the tape recorder. He was quite embarrassed about the idea. So he sang me ‘The Old Cross Of Ardboe’, which is a very famous Irish song from around Lough Neagh, and he sang it from behind the privacy curtain that was pulled round his bed. He was actually sitting on the bedpan at the time, which you can hear clanking in the background! I’ve still got the tape recording somewhere. The recordings in the hospital were the beginning of something for me, I realised that there were people singing this music out there, so I became determined to seek it out and got really excited about collecting it.

I understand that you developed your interest in traditional music further at University, and became more active in trying to bring it to a wider audience by starting a folk club there?

John Moulden UFMS c1966 – photo with permission belfastfolk.co.uk

Well by ‘62 I had decided to go to University, so I went to Queens in Belfast to study for a diploma in Social work. I wanted to meet people who sang and played this sort of music and I’d go along to the folk club in Belfast. I never sang there but I met people like John Moulden and Den Warrick. I also naturally gravitated towards a club at the University called the Glee Club. Phil Coulter, an interesting guy who was already known as a record producer even as a student, was in charge of the Glee Club the year I arrived and it was always a superb show. They would fill the Student Union and everyone did a turn; music, poetry readings, comedy acts. They had great people on like The McPeakes, and Phil had a very good band that would play. I performed a few times – mostly Woody Guthrie songs.

Phil wanted me to become the chairman of the Glee Club after he stepped down, but I didn’t win the vote, for various reasons. I knew I couldn’t have done as good a job as him though, so I wasn’t too disappointed. Because Phil was already known in the music business he often managed to persuade touring musicians to come and perform. When any big stars were playing in Belfast, he would go down and get these people to come up and sing a song at the Glee Club; he even tried to get the Beatles at one time but it didn’t come off. Anyway I didn’t get that position, and I was actually quite relieved because it really was a full time job. So at that time I decided I’d start a folk club – this would have been around the beginning of ’63 – because I’d met a lot of people in the University who were also keen.

So a number of us at Queens formed a folk music society. We had a committee with people like Manny Aharoni, Judy Silver, Eugene McEldowney and Sean Quinn, a fine accordian player. Quite a few were involved, and I took on the organisational side. We met at the university anatomy museum, where we sang surrounded by skulls and pickled body parts, which made for an interesting atmosphere! Actually the person who ran the anatomy museum later became a very well known author, Bernard MacLaverty, but we just knew him as the guy in charge of the museum. There were a lot of good local singers around – I remember Henry O’Prey well, a great character and Gaelic singer who sang English songs too. We filled the place and it was great, very successful.

I ran the club for one year because I finished my diploma, left Queens and went to the London School of Economics, where I took a further qualification to become a psychiatric social worker. The folk club was left in very good hands though. In London I met a lot of interesting people; I got involved with Eric Winter who ran a folk magazine and I also sat on a committee organising the first National Folk Festival. I’m not at all sure how I ended up on that committee: it’s all in the dim and distant past.

The National Folk Festival was run at Keele University, in Stoke on Trent, and I got to know Rory McEwen, a lovely man who used to sing on the magazine programs I mentioned previously (he always used to sing Bonnie George Campbell, one of my favourite songs). Rory was a great organiser. That was a big opening moment for the festival because they had a lot of traditional singers, not just revivalists, and they had people like Bert Lloyd and Ewan MacColl giving lectures. I think that was probably when I first got to know Ewan. I used to go to Islington Folk Club London that Bob Davenport ran, which was completely different to Ewan’s club. Bob’s club was very laid back while Ewan’s club was very controlled. Both were great clubs though. They were exciting times. I do have a vague recollection of meeting Bob Dylan around that time, but I have to say it’s pretty vague – quite possibly a dream!

I know Ewan McColl was encouraging to you, and I gather he gave you access to some recordings that he’d managed to get hold of?

Yes, I was spending a lot of time searching more for Ulster or Irish songs and at one point I remember going along to Cecil Sharp House because they had a collection of songs that had been done by the BBC in the 1950s. It was a really big collection of songs from throughout the British Isles; recordings by Hamish Henderson, Sean O’Boyle, Peter Kennedy and all those collectors. You could go in and listen to the collection but you weren’t allowed to copy them. I wanted to bring in my tape recorder and record some of the songs in order to listen to them properly and learn them, rather than just writing down the words and trying to remember the tunes. It wasn’t allowed though; they would only let you hear them. I got really frustrated about that. I remember complaining to Ewan about this, and he said “don’t worry, I’ve got the full collection at home on tape and you’re welcome to copy them”! So he opened his box of goodies to me and I went over and recorded whatever I wanted, which was very generous of him. It certainly set me on the path because I began to realise at that point that there were an awful lot of songs and singers still alive – traditional singers, not just revival singers as we were calling ourselves – and it became clear that the actual tradition wasn’t dead. It was hidden, but it wasn’t dead.

So when you left London, and went back to Belfast, you became even more involved in the traditional music scene and set up another folk club?

Yes, I went back from London qualified as a psychiatric social worker and began working in child psychiatry, which was very interesting. Of course, all the people from University had gone their separate ways, but they were still mostly around Belfast. The Queens University folk club was still going strong, and I went along to sing and still organised a few concerts for them. John Moulden and myself, along with Dave Scott and Terry Brown and other musicians and singers who were amazingly active, decided to open a rather grandly named ‘Ulster Folk Music Society’ (UFMS) in an old building in Donegal Street. We had a variety of Ulster performers and organised concerts. As well as the songs, I wanted to get some traditional musicians to play because my real desire at that point was to mix the singing with music. It seemed to me at that point you could go to sessions of Comhaltas and so on but there would be no singing, there would just be traditional music. Or you could go to singing sessions and there would be no music, just song. That was one of my big ‘things’, I think even in the early days at Queen’s. There were lots of folk clubs in Belfast doing various things but my thing was that I wanted the music and song to be together – it seemed to be a ridiculous situation.

Tommy Gunn (Photo: Robin Morton)

I think it was Henry O’Prey who had introduced me to Tommy Gunn, who just lived around the corner from Queens, and Tommy became a regular at the UFMS. Tommy, who was from Fermanagh, was a great fiddle player and carrier of tunes. He had in turn introduced me to a young Fermanagh flute and whistle player called Cathal McConnell, and I was just amazed at this incredible musician who had been All-Ireland champion for both instruments by the time he was 18. I’d stayed in touch, and used to get Cathal to come over to Belfast to play at the UFMS, along with other great musicians like Paddy Tunney, Leo Ginley and Sean Quinn. I got Bob Davenport, Peggy Seeger and Ewan MacColl to come over and perform, and arranged tours for them. We had a lot of good singers and it was my desire to keep the music and songs connected. There were some wonderful players; I met John Rea the hammer dulcimer player – an amazing man and musician. Nobody had ever heard of a hammer dulcimer player playing Irish tunes at that point! John worked on the tugboats and was from the Glens of Antrim. Tommy also introduced me to Sean McAloon who was a great piper, originally from Fermanagh. Sean was a very quiet, gentle man, and we got him to come and play too.

This is obviously well before Temple Records existed, but were still you beginning to think about recording music for release in those days?

Yes, there was a real lack of traditional recordings available at the time, and I decided to try to do something about it. It took a while though; it was 1970 before I was actually managing to get things released. Actually one of the earliest releases was ‘Drops of Brandy’, a recording of John Rea and Sean McAloon. I produced it, and we recorded at Tommy Ellis studios in Dublin, The pipes and dulcimer were just superb together. That came out first on Mercier, the Irish publishing company and Topic Records later re-released it, but it was very difficult to get them interested at first.

Prior to that release though, I actually remember putting together Cathal McConnell, Tommy Gunn, Sean McAloon and John Rea round a Brenell tape recorder in the apartment I was living in. I made an appearance myself too, playing a bit of bodhran which the recording would have been safer without! I recorded some traditional tunes and sent it to Topic, which Bill Leader was in control of at that point. I wanted to convince them to put out traditional music – there really wasn’t any available then; they were issuing folk revival recordings. I remember getting the letter back from Topic saying that they weren’t interested, but when I tried to get the recording back I found they’d lost the tape! I’d love to hear that recording now. The experience made me more determined than ever that this music should be available to a wider audience, and it’s something that was in my mind later when I set up Temple.

So having now met Tommy Gunn and Cathal McConnell, was this mid/late sixties period the very early days of Boys of the Lough?

It was early days, and we weren’t using the name, but it’s where it started. I had started to play with Cathal and Tommy during this period. These two guys were already playing together and I suggested we might work well as a trio; they could show off their music and I would sing a few songs and play the bodhran. Tommy was a great character and musician. A dancer and lilter, he also played the bones and the fiddle and told a good story too, or as my Uncle Tom used to say, he ‘told lies’! Cathal was a superb musician and I was the man sitting in the middle oiling the cogs – singing a few songs, playing bodhran and concertina – it just seemed to work. Actually, I think the first tour we did as a trio was organised by Ewan MacColl – or Peggy Seeger probably. They did a tour for us where we played Ewan’s Singers Club and some shows in Scotland and England. I remember our first gig was in Livingston in the middle of winter – an alien environment indeed!

As a trio, we did three or four tours together and played quite a few festivals, mainly in Scotland but also in England. The traditional singers were now beginning to appear at these festival, and not just the ‘revivalists’. I remember we played at the Inverness folk festival and folk club a couple of times. We played in Edinburgh and met Hamish Henderson, who became a good friend later. They were exciting times and we met amazing people. I remember one night – we’d done maybe two or three tours at this point – when Cathal asked “would you mind if I sing a song?”. As far as I was concerned he was ‘just’ this great young flute and whistle player – still in his early twenties probably – and I’d no idea that he sang. So he sang that night and, God Almighty, what a singer! That first song was ‘Matt Hyland’ and it made the hair stand on the back of my head. Just amazing. There seemed to be no end to his talents.

We made a bit of a reputation for ourselves after a few tours but we weren’t going out under a ‘group’ name until we played at Aberdeen Folk Festival. It was a very good festival, run by the late Peter Hall who had a singing group which made excellent recordings; Tom Spiers and so on. Peter booked us and wanted to give us a name rather than billing us as ‘Cathal McConnell, Tommy Gunn and Robin Morton’, so without a great deal of thought, we just called ourselves ‘Boys of The Lough’ after a reel we often played.

Tommy Gunn eventually retired from touring after a few years though; he was a lot older than we were and he liked his home comforts. I liked Tommy very much, and every time I went home I would see him. He was such a great musician and character, and we really got on well together. Cathal and I continued to tour and play together after Tommy left; we’d already recorded an album as a duo in 1969, ‘An Irish Jubilee’, for the Mercier label. So that was the early years, before we became a four-piece and things really took off.

I gather that you also became involved in broadcasting as well during the sixties, working with the BBC and others. How did that come about?

In ’67 I had decided to go back to Queen’s University to do a degree in Economic History. At the same time I was working in broadcasting to support myself – I needed money because I wasn’t getting a full grant. I had previously had some involvement with radio; when I was at Queens I’d put together a short documentary program for the BBC based on Ewan MacColl’s radio ballad format; songs, music and recorded interviews. Maurice Leitch, the author, was at BBC Northern Ireland in those years and he produced it. It was based on unemployment in Belfast and it showed what a dreadful situation the city was in at that time. The unemployment level was 10.5-11%, and nobody seemed to give a shit. The stories of these men who found themselves without work were really moving.

So, to fund this degree, I was doing human interest interviews for the BBC in Ulster for the early morning magazine programme, under the name of Robin Morton. Also, at the same time, I would sell another similar interview of the same story (a completely different interview mind you) to RTE under the name ‘Robert Martin’. I remember Cathal telling me there was a guy on RTE who sounded just like me! I don’t think I ever explained, so he still probably doesn’t know it actually was me! I was also sometimes selling a third interview of the same story; Gloria Hunniford – the ‘Queen Mother of broadcasting’ – and I went to school together and we’d kept in touch. So I used to sell her some of these interviews for the BBC World Service. So that was quite a nice little earner to fund student life, and interesting as well.

I’d done some television work too; in the mid 60’s I had been appearing on a mid-afternoon TV program on UTV (singing those Woody Guthrie songs I really loved) and then while still at University, I was working as the link man for the BBC TV evening news programme. I was offered a full-time job in the BBC but I knew I didn’t really want it. Even at that time, I realised it was a kind of cultural civil service and really wasn’t for me. I wish I had taken it – I’d now have a pension! Anyway, I worked on the news programme for about a year, but I was starting to worry that it was taking up too much time and I wasn’t going to get a good degree. I had a research project I wanted to do so I needed to focus. The ‘opportunity’ came on a live programme when I had a falling out with a director. I had asked a question which he didn’t like and he said he was going to have to write out the questions for me in future. I didn’t think that was the way it should work and got out at that point. I got the 2:1 degree I needed and the man who took my place, I’m proud to say, was Nick Ross, who became a very good broadcaster – much better than I ever would have been!

You were obviously juggling a few balls and keeping busy, but were you still working at collecting songs as keenly at the same time?

Yes, absolutely. At the same time as studying, working and performing, I was still going out there collecting and recording songs. Not long after I had come back from London in 1965 I had gone to the Ulster Folk Museum to try to persuade them to invest in a really good tape recorder so that people like myself, John Moulden, Terry Brown and anyone else with an interest could use it to collect songs. The idea was that we could borrow the tape recorder and give them copies of the tapes so they could build up an archive for the Ulster Folk Museum. I wasn’t into the archival side but I just wanted to get the songs before they ‘died’ and were buried and forgotten. The Folk Museum were doing an amazing job; saving and conserving old buildings, churches, cottages and so on – if you’re ever there you should go and see it – but what they weren’t doing was paying attention to the music or songs of Ulster. Anyway, I went along to see the director George Thompson, who was a very nice man, and we had a good talk but it became clear it wasn’t going to happen when he asked me “what qualifications do you have for doing this?” It really seemed a very shortsighted approach. The clock was ticking on some of these songs and singers, and I thought that enthusiasm and a real interest in the music should have been qualification enough.

Anyway, I ended up just getting myself a decent tape recorder and kept on collecting and recording. I collected songs from many fine singers – great people who could ‘tell’ a song like a story, not just sing it – like Dick Bamber, Elly and Peter Mullarkey, Tom Todd, Davy Menish, Sally McCreevy, Paddy McMahon, Arthur Whiteside and the Maguires – Brian, Biddy and John. I spent a lot of time at John Maguire’s farm; he really was a fascinating man and I later collated his songs and stories of his life in a book (‘Come Day, Go Day, God send Sunday’, recently re-released by Routledge) with an accompanying record.

At this point though, I was working on compiling a collection of songs for a book: ‘Folksongs sung in Ulster’. I had come back from London really driven to get people to sings songs from Ulster, probably fired up by Ewan MacColl, who always said that you’ve got to go out there and sing songs from your own area – even though he didn’t really do it himself. I always found it a bit strange that Ewan was so adamant about this, but didn’t quite do that himself. Anyway, I was driven by that idea and I really wanted to get people singing these songs.

I had spoken to a song collector who was well known in Ulster and said to him “you’ve collected a lot of songs, why don’t you put out a book out to let people get hold of them and sing them”. I thought it would be good to get the songs back into the community rather than being hidden away. His response, which really surprised me and actually made me quite angry, was “aw, no, you don’t want to do that because they’ll spoil the songs”. At that point I decided, well sod this, I’m going to compile a book of the songs I’ve collected and get it out there. So ‘Folksongs sung in Ulster’ was published in 1970 together with two accompanying albums of original traditional singers; Folksongs Sung in Ulster Vol.1 & 2 (Mercier)

This would be around the time that you left Belfast, and moved to Scotland for long term?

Yes, it would have been late 1970 when I went to Edinburgh. I wanted to study for a PhD, and I’d previously thought of Warwick, because E. P. Thompson was there. I had an interest in ‘wife selling’ songs, which was a topic of his, but he had left by this time, so I thought Edinburgh would be a good choice. There was a flourishing folk scene there and I was interested in the connections between Scotland and Ireland. Obviously, the musical connection between the two was strong. From an academic perspective, I was interested in the history of madness, and the historical connections between treatment in the two countries. So that was the next step on the road. My PhD never got completed in the end – life ended up getting pretty busy in the seventies!

Note from Robin: It was a busy time, a good few years ago, and my memory of it all isn’t perfect, so please do forgive any errors or omissions.

All photos are from Robin Morton’s collection except two: ‘John Moulden’ and ‘Robin Morton, Gillian McPherson and Tommy Gunn’ which came from www.belfastfolk.co.uk and are used with permission.

Thanks to Fergus Woods and Brendan Fulton for providing extra memory power & for the use of photos from www.belfastfolk.co.uk

Thanks to Pete Heywood for the main feature image.

You can find out more about Robin Morton’s Temple Records label at www.templerecords.co.uk

I loved Robin’s singing voice and you can hear him performing Jackson and Jane on our Folk Show (Episode 99), it’s a Co. Monaghan song from Frank Smith of Rockorry. We also featured Robin singing ‘General Guiness’ in our Folk Show (Episode 70), a vaudeville song that extols the virtues of Ireland’s “black liquidation with froth on the top”…Robin learned the song from Dick Bamber who lived in his native Portadown, Co. Armagh.

Robin Morton: 24 December 1939 – 1 October 2021

Robin Morton Death – Obituary – Dead News: So sad tonight to hear of the passing of a great friend, Robin Morton – a fantastic musician, trailblazer and true gentleman

https://celebritiesdeaths.com/robin-morton-death-obituary-dead-news-so-sad-tonight-to-hear-of-the-pa...

Robin Morton sings The Newcastle Fishermen

https://youtu.be/pS0yjzu3uCg