BY ZACH MORTICE

One of the most startling projects submitted for the 2020 ASLA Student Awards was Dark Matter—a proposal that uses landscape as a transmission medium for the ecological values of the deceased.

With arresting images and a somewhat unconventional project type, Dark Matter dazzled the jury, which bestowed the Award of Excellence in General Design on the project last spring. John Whitaker, Student ASLA, an MLA candidate at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis, designed a proposal that created a memorial landscape that grows over time to unify human remains with nonhuman ecologies, promoting biological and cultural diversity and offering mourners “the continuation of a relationship that would endure over time with both their loved one and the larger site,” Whitaker says.

John Whitaker, Student ASLA. Photo by Rachel Whitaker.

It’s a somber and subtle approach that stands in contrast to typically Edenic and chipper visions of green burial—the practice of interring the deceased in a biodegradable casket and shroud and letting decomposition take its course. The site is the Old St. Marcus Cemetery in St. Louis, part of a long chain of more than a half-dozen cemeteries near the city’s southern edge. Old St. Marcus became a city park (called St. Marcus Commemorative Park) in 1977 after bankruptcy and years of neglect, but only families that paid for perpetual care or paid a fee when the property changed hands made the move to the new site, and most interments were left in place. Today, Whitaker says, grave monuments are still scattered about in various states of disrepair, consumed by turf or damaged by maintenance vehicles.

Dark Matter is both a process and a site-specific approach to managing the landscape. It begins with the Recompose burial method, which Whitaker proposes would happen on site. Pioneered by Katrina Spade, the Recompose process differs from traditional green burial because it expedites decomposition aboveground. It begins by laying the deceased in a cradle surrounded by wood chips, straw, and alfalfa. The cradle is placed in a Recompose vessel and covered with more plant material. The deceased’s body and the plant material remain in the vessel for 30 days as microbes break everything down at a molecular level, transforming flesh, blood, and bone into a cubic yard of nutrient-dense soil that is allowed to cure. By controlling for moisture, carbon, and nitrogen levels, this exothermic reaction (temperatures in the vessel can rise above 120 degrees) expedites the decomposition process. And it saves a metric ton of carbon dioxide each time, compared to cremation or traditional burial.

All the gradations of landscape type and program across the entire site flow from the ecological and spiritual worth of these decomposed remains. To Jacqueline Margetts, Whitaker’s faculty adviser, the landscape is an answer to the question: “How do you honor that material?” she says. “He was so thoughtful in the way that he wanted to acknowledge the value of the material from an emotional, personal point of view.”

The deceased’s remains are placed in cylindrical sarcophagi that decay over time, creating a mound topped with plantings. Image courtesy John Whitaker, Student ASLA.

With Dark Matter, mourners place their loved one’s remains in a low-fired ceramic cylinder sarcophagus in the landscape, which will “endure just long enough,” Whitaker says. The sarcophagus can then be planted with a tree or other flora. Over time, the wooden bottom of the sarcophagus decomposes, and after the 10-year mark, the rest of the sarcophagus does as well, depositing a sculpted mound on the land, with the selected plantings or tree acting as a grave marker. The mound form coaxed through the cylinder shape is meant to be an implicit reference to the Indigenous, millennia-old Cahokia Mounds just across the Mississippi River, which was the largest precolonial settlement north of Mexico. Whitaker says he didn’t want to lean into this history too heavily lest it veer into cultural appropriation. But by nodding to these elemental landforms, the proposal reflects the timescale of this landscape.

The deceased or their loved ones select the plants and trees instead of choosing from a narrow list of acceptable plants. Whitaker says that he wants people to have a free hand in determining the composition of these places, selecting plants to express the idiosyncratic and personal nature of burial symbols. “There’s a lot of coded messages and coded cultural language in specific plantings, especially in African American cemeteries,” he says. And since these coded references aren’t all familiar to him, he wanted his plan to offer maximum expressive flexibility to “build the biodiversity of this site, but also make it extremely personal for them.”

Though Whitaker delineates several different landscape types across the site, the aggregate result will largely be determined by the planting choices the deceased and their loved ones make. Image courtesy John Whitaker, Student ASLA.

Whitaker sees the need for a consulting ecologist to work on site, and he delineates a handful of landscape types (grassland, woodland, gardens, a wet meadow). But beyond that, it would become a landscape primarily defined by what’s decomposing there, and the plantings and their placement are the product of disparate individuals united mostly by death. It’s “an emergent landscape that is setting up a framework but is not overly concerned with a predetermined outcome,” he says. “This is an acknowledgment that natural processes are messy and have an unpredictability that you can’t direct,” says Margetts.

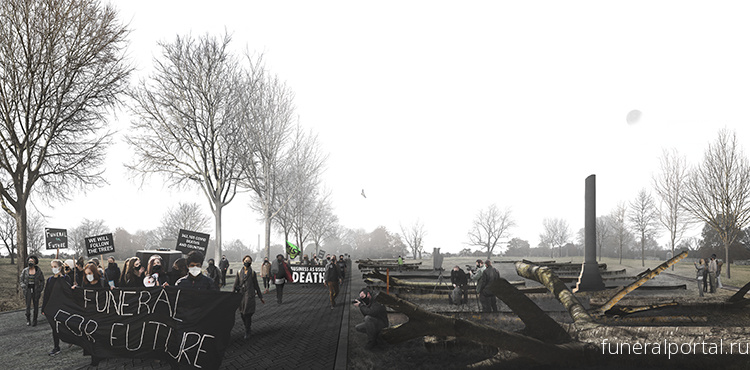

To kick-start this process, Whitaker calls for ash trees decimated by the emerald ash borer to be distributed across the site so their trunks can provide nutrients as they decay. These felled tree trunks would slow precipitation and runoff in a flood-prone area, alongside prairies and reinvigorated plantings. And in Whitaker’s renderings, they also lend an air of entropy and despair: doom pillars knocked to the ground. “Their concentrated presence will initially register as a visible tabulation of the city’s loss and a warning against future ecological catastrophe,” Whitaker wrote in his project narrative.

Whitaker depicts moments of joy and warm remembrance, but for the most part he “[leans] into the melancholy setting,” he says, designing a landscape that is an epitaph for its age. There are crimson skeletons and charcoal sketches of cremation chambers, illustrating carbon-huffing interment practices that are part of the problem. In his renderings, Whitaker illustrates the Dark Matter landscape as a forum for collective civic action, but judging from the protest banners in his renderings (“Funeral for Future,” “We Will Follow the Trees,” “342,105 COVID Deaths and Counting”), this fight has already been lost. The project’s most radical move might be proposing a memorial landscape that’s not idealized but is instead firmly grounded in its grim ecological and political moment; neither an ode to the great deeds of the past nor the assumed resolution of the current day’s crisis. It seems like a project tailor-made for a period defined by pandemic-induced mass death, but the most emotionally poignant elements of the plan were derived after a climate crisis inflection point that’s not likely to be well remembered in the run-up to COVID-19: the Australian wildfires of late 2019 and early 2020. Even with no personal connection to the wildfires, he felt “enormous sadness and loss” and “helplessness,” Whitaker says. At that point, he integrated the felled ash trees into the plan and strengthened the connection between ecological loss and personal loss. “That was pivotal in making this project have more gravity to it.”

Decomposing ash tree trunks become a visual reminder of community loss and a source of nutrients for emerging landscapes. Image courtesy John Whitaker, Student ASLA.

Dark Matter focuses on new ways to build ecological consensus, which by the time span of the project could very well take centuries. Whitaker has described it as a decentralized “memorial system” instead of a traditionally “static site” of grief. And in several ways, Dark Matter expands the circle of grief and compassion from the individual to the wider world, linking expressions of grief. By situating the remains of a loved one very literally within the ecology of the site, it links the pain caused by the loss of an individual with the trauma and dread of dwindling biodiversity and mass extinction.

Anyone who raises their hand to become biotic matter nurturing plants in an experimental landscape understands the ironclad necessity of planetary stewardship. As loved ones plant and monitor these developing landscapes over time, they’ll become immersed in the same responsibility. Whitaker says, “I love the idea of seasonal burnings, plantings, removal of invasive species—all of those becoming a way of engaging with your loved one’s memorial.”