In Conversation with Daniel Browning

Yhonnie Scarce is a master glassblower known for sculptural installations, which span architecturally scaled public art projects to intimate assemblages.

Born in Woomera, South Australia, Scarce belongs to the Kokatha and Nukunu peoples. Family is central to her practice, which draws on the experiences and strength of her ancestors underpinned by extensive and in-depth research into wider cultural, colonial, and global histories.

In particular, Scarce looks at the displacement and relocation of Aboriginal people from their homelands, the removal of Aboriginal children from their families, and the ongoing impacts of the British nuclear tests undertaken in South Australia during the 1950s, all of which are central subjects to her exhibition Missile Park at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art in Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021).

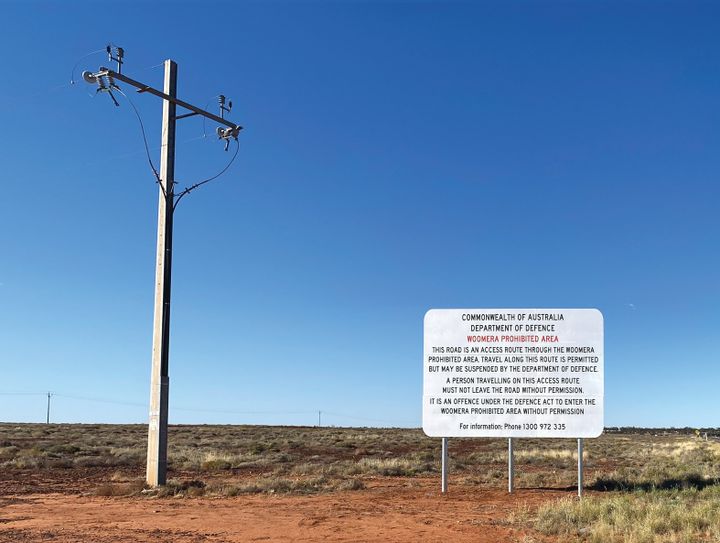

Yhonnie Scarce, Prohibited Zone, Woomera (2021). Research photograph. Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne.

Australian Centre for Contemporary Art Melbourne VIEW INSTITUTION

Included are works spanning the past 15 years, like early pieces such as The Day We Went Away (2004), made during the artist's final year at the South Australian School of Art and comprising a collection of glass bush bananas in a found suitcase, referring to the displacement of Aboriginal communities and the imposition of colonisers and missionaries.

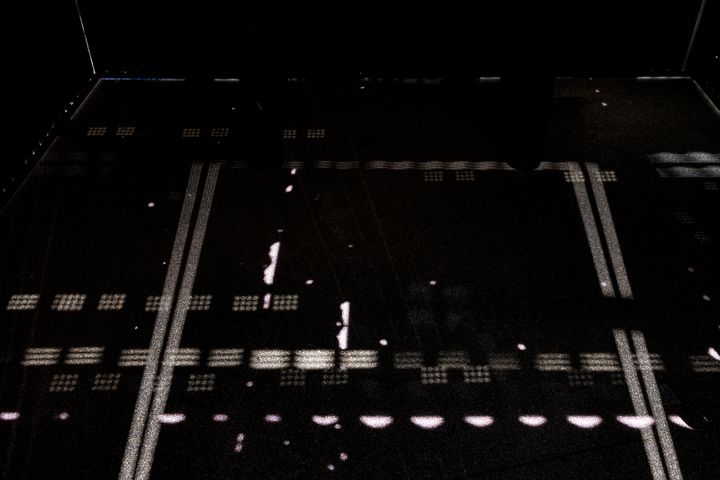

Also on view is the artist's commission Missile Park (2021)—an installation of three sheds salvaged from a scrapyard and painted with bitumen. In their darkened interiors, streams of light spill through small perforations, and viewers find black glass sculptures, their surfaces glossy and rounded. As the artist explains in this interview with broadcaster, freelance arts writer, and sound curator, Daniel Browning, 'The truth is in those sheds. They're waiting to be unearthed'.

Initially held on 29 March 2021, Scarce talks to Browning about the themes explored in Missile Park and Scarce's practice more broadly.

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park (2021). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

I want to read something back to you that I wrote in relation to a work that was commissioned for The National in 2017 and exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales: 'In the suspended wraith-like clouds, we are temporarily blinded to the lingering effects of the British nuclear tests on Aboriginal land across much of inland South Australia in the 1950s. On close inspection, the beauty of the work is subsumed by a deeper sense of national unease, of the excesses of blind ethno-nationalism, the flagrant disregard for human life and indifference to environmental destruction of which nations are capable.'

YSI used to be quite embarrassed about where I was born. I'm one of five children and I was the odd one out. I was born on a military base, and it was something that I found quite a lot to confront. I remember my mum taking me there during a road trip from Alice Springs to Port Augusta to visit family. I pulled up and I was like, 'Geez...'

I was 16 at the time. But now I feel like it's part of my history. I keep going back as much as I can to unearth what is lying out there.

Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

YSDefinitely. I remember the last two years of my visual arts degree, I was trying to figure out what was going on with them. When I was training as a glassblower, there was this idea that you would move on to do more functional objects. I couldn't see my culture being in a drinking vessel or something like that. I was making bush food to represent something, and for me it was a perfect representation of us: the food that we eat.

Yhonnie Scarce, Blood on the wattle (Elliston, South Australia, 1849) (2013). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased with funds donated by Kerry Gardner, Andrew Myer and The Myer Foundation (2013). Photo: Andrew Curtis.

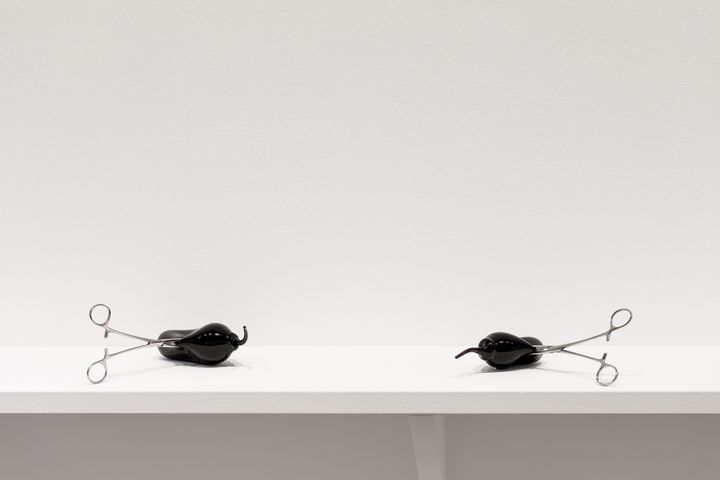

YSThe bush plums that are situated in Missile Park are exactly that. When I was thinking about the new commission and what kind of glassware could sit inside these sheds, the bush plum was perfect, because you can create them on a larger scale and larger form. I kept thinking about what they would look like inside the shed.

It was always obvious that they were going to be black as well. When I think about bombs, they're not always going to be the usual thing that comes out of the sky or out of a plane. For me, it was something more grounded. The plum looks as if it has a wicker ready to be set off. The truth is in those sheds. They're waiting to be unearthed, or ready to go off.

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park (2021). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

DBI often look at the bush plums, which are rounded and have a long tail, in relation to an installation you made called Fallout babies (2016), presented at THIS IS NO FANTASY for your exhibition Strontium 90 (6 September–1 October 2016). The bush plums in this work reminded me of reproductive cells.

YSYes. At that time, I had just returned from Woomera and was researching the deaths of babies there, and thinking about all the Aboriginal babies that were unaccounted for. At Woomera cemetery there's quite a lot of children. It's disproportionately a children's cemetery. Back when I was first doing that research, the nuclear tests were not being blamed for these children dying. It was always blamed on the weather and all the extreme conditions. But I was born there in 1973 and I'm still here.

Yhonnie Scarce, Strontium 90 (2016). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

When we travelled there in early January 2021, it was 45 degrees. It's harsh, but I don't think it would kill that many children. Also, the children in the cemetery are probably only a quarter of those who have been lost up there. I can imagine that with Aboriginal children, we wouldn't even know what happened to them.

I used the image of that cemetery with the fallout babies and used the plum as a representation of the different gestational periods of pregnancies, from the really early embryonic stage to full term. Those bush plums were also sandblasted white because they no longer technically exist, physically.

Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park (2021). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

YSI wonder if they ever will. You think about the current Australian government and its current state right now. I think it's something that is yet to be fully acknowledged. Malcolm Turnbull gave Aboriginal people a veterans gold card for healthcare, but it was too late. The majority of them are dead now. There's an entire intergenerational trauma, with people and their descendants being affected by radiation poisoning. Where does that leave them?

Yhonnie Scarce, Weak in colour but strong in blood (2014). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

Family is a key part of your practice, and it's where a lot of things often begin for you. Has family, and representing them, always been something that has driven your practice?

YSDefinitely. I think they're always circling around. It's something that is really important for me to talk about in my practice. I'm very lucky to have family members and cousins that are searching for photography and old photographs, because it can be very difficult to get a hold of images from the institutions that took photos of us, or my family, in the early days.

There's an entire intergenerational trauma, with people and their descendants being affected by radiation poisoning. Where does that leave them?

I grew up with that knowledge of my grandparents being really hard workers. They put up with a lot of shit: had to always ask permission to travel, and lived below the poverty line. But at the same time, they've strongly retained their culture. I always like to acknowledge them in that sense, because if it wasn't for them, I wouldn't be where I am today. They stood up for a lot of things and I think they came out a lot stronger in the end, and so did I.

Yhonnie Scarce, Weak in colour but strong in blood (2014). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

I want to talk about the image of Granny Dinah, which is for me one of the most electric and moving images in the exhibition, but also across your practice. I think that photograph was taken by Lutheran missionaries at Koonibba?

YSIt's unclear who took that photo. It's an ethnographic photograph. I wanted to create a work about her, but I didn't want to use the actual photograph, because I felt like it was really disrespectful. For me it was about the way she looked at you and that was really important, because she's my main matriarch besides my aunties, grandmother, and my mother. It is a big honour to have her here.

Yhonnie Scarce, Working class man (Andamooka opal fields) (2017). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

YSThe first one was exhibited in a collateral event for the Venice Biennale in 2013. I was also invited to create a work for Melbourne Now at the National Gallery of Victoria shortly after, and they were very interested in the coffin. At the time, I was reading Blood on the Wattle (2003) by Bruce Elder, so we asked permission to use that title for both works, and he was very generous and allowed that.

Yhonnie Scarce, Blood on the wattle (Elliston, South Australia, 1849) (2013). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased with funds donated by Kerry Gardner, Andrew Myer and The Myer Foundation, 2013. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

I wanted to go back to South Australia again because, for those who don't know, a lot of massacres of Aboriginal people were not—and are still not—well documented, in South Australia in particular.

In Elliston, South Australia in 1849, there was a group of Aboriginal people who were run off the cliff at Waterloo Bay for stealing a sheep. They say that only 30 people died, but I have always believed that there were more. They were probably shot beforehand too. And there were children as well. For this coffin, I created two mounds in it to represent that cliff face.

Yhonnie Scarce, The day we went away (2004). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Private collection, New Zealand. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

YSI visited that memorial for the first time in 2008. I had won an art award from South Australia [the Qantas Foundation Encouragement for Australian Contemporary Art Award] that enabled me to travel there. That visit heavily influenced my work. I was only two or three years out of art school, so it was the beginning of fieldwork research for me too. It was an important place.

I called Berlin memorial city, because there are memorials all over the place there. That particular trip made me think about the lack of memorials in Australia for First Nations people, particularly regarding frontier wars and the bigger picture of genocide. I started creating specific works related to massacres after that.

Exhibition view: Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

YSI've been working with an architect, Mikhail Rodrick, for quite a long time. We worked together on Missile Park, the new commission, and he's been around for nearly a decade with me. With Edition Office, I knew they wanted to work with me, and it was just a matter of when. We have a mutual friend, Daniel Boyd, who they've worked with before.

Yhonnie Scarce, Florey and Fanny (2012). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

I was on a research trip with Lisa Radford, my colleague at the Victorian College of the Arts, in Tbilisi in Georgia when Kim Bridgland of Edition Office approached me about the NGV Architecture Commission. We were already looking at former Soviet Union architecture at the time. I've been interested in brutalist architecture for a long time, specifically the Spomenik throughout the former Yugoslavia. When we started talking about the NGV Architecture Commission, it was also always obvious that it was going to be about Aboriginal infrastructure.

I memorialise my family and I create a space for them to be remembered, not just by my family, but for others as well, because I think Australia is very good at forgetting the past.

We'd been talking along the way while I was travelling, for I think six weeks, doing FaceTime and things like that. It was something that we felt needed to have a presence in the garden; not only to respond to it, but to use it as a platform. It was always going to be quite large. It was originally meant to be 15 metres high. It ended up being nine metres high, but it was big enough anyway.

YSIt was something that I didn't really think about until we were talking this afternoon, because I'm in it all the time. I'm very specific about memorials and how they should look. But you're right. I memorialise my family and I create a space for them to be remembered, not just by my family, but for others as well, because I think Australia is very good at forgetting the past. You and I have talked about this amnesia, and it's easy for people to forget. So I create work to not forget. I guess that's the memory part of things.

Yhonnie Scarce, The collected (2010). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Collection: National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne Purchased by NGV Supporters of Indigenous Art (2011). Photo: Andrew Curtis.

YSThese are scaled-down military buildings. For me, it was about creating a space where you get the idea that it could be military, but also the military cover up of Aboriginal deaths in South Australia during the nuclear tests and how the Woomera prohibited area was implicated in that too, because who knows how many Aboriginal bodies lay out there. I wanted to create tomb-like structures as well.

There is one space in particular where you are faced with glass sculptures that stand in for Aboriginal people sitting inside. I called them the dirty little secrets, or the House of Horrors, because you do hear stories about the ground being opened up and Aboriginal bodies being rolled in. It's a pretty disgusting part of South Australian history and Australian history in general. The sheds themselves, for me, they're disintegrating. It's just a matter of time before the secrets come out and those little time bombs go off. It's sort of like you're forced into that darkness as well.

Yhonnie Scarce, Weak in colour but strong in blood (2014). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

YSI was doing a residency in Birmingham last year with Ikon Gallery, which has been postponed until next year. I was invited to do the residency specifically because it was about my research into the nuclear tests in South Australia. At the Breakaway bomb site, I was told by an academic at the University of Birmingham that a lot of people think that because that particular bomb test was low to the ground, they thought the ground had turned to glass before it had actually gone completely off.

The topsoil of that site was elevated into the air, and it became molten and then it was slapped back down on the ground. That's how intense it was. There are still remnants of glass that have been left behind, though they supposedly did a clean-up in the 90s. But the three times I've been back, that glass is starting to disintegrate and return to the ground, so there's less out there, unless tourists are stealing it. But yeah, I wouldn't be doing that.

Yhonnie Scarce, Weak in colour but strong in blood (2014). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

DBIt's radiated. And it crackles under foot, doesn't it?

YSIt does, and it glistens in the sun. It's beautiful, but it's weird at the same time.

DBIn the hot shop where you're blowing glass, the temperatures are infernal. How hot does it get?

YSI guess it depends. It can be between 1,200 to 1,700 degrees in the furnace. It's burning hot. I make work at the Jam Factory and that studio is pretty large. But during a hot day, when there are four burners or four benches going, you feel it. It's pretty extreme.

Yhonnie Scarce, Nucleus (2020). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

YSYeah, I didn't realise what they did out there until I visited. All the bomb sites that you see out there have been covered up. There are planes, trucks, landrovers, buildings, towers, and probably human beings, honestly. I think there are four pits out there and they're large. They dug the ground five kilometres deep before encasing everything. Uncle Robin Matthews, who does the tours out there, he has to do boundary checks of those tombs to make sure that they're not disturbed, because otherwise the radiation will start to rise.

Yhonnie Scarce, Weak in colour but strong in blood (2014). Exhibition view: Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

YSYou're told that it's low levels, but they say you can't really live out there for too long. It's similar to Fukushima and Chernobyl. You have low levels of radiation, so it's not recommended to kick up the dirt or anything like that.

DBWhen I first met you, 10 or 15 years ago, you were creating all these forms that were lustrous and beautiful and sensuous. And then you got to a point where you started to pierce them. You started to break the surface of the glass. Some of the works presented at Tarrawarra Museum of Art for Looking Glass (28 November 2020–8 March 2021) had holes in them. So you've kind of gone on this trajectory of subjecting the medium to as much stress and pressure as possible to kind of exhaust it.

YSThe objects are quite beautiful, you don't really want to disturb them, but then at the end of the day, for me it's important to tell the story right. One of the works, The Cultivation of Whiteness (2013), I cut up, and a lot of people were telling me not to, because they're beautifully lusted. I didn't go too mad, but it's enough I think.

Yhonnie Scarce, Hollowing Earth (2017). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

DBI think that destruction is very interesting. It's very evocative.

YSYeah, I think so. At first I felt bad about it. I do often have glass pieces that have cracks in them, but they can't exist because they're already disintegrating, so I don't want them around anymore. I smash them, but I'm sure they understand.

Found objects and other materials are a large part of the process. I'm not a glass artist, I'm an artist who works with glass and other materials.

DBYou describe your relationship to glass as being like a love affair. You also refer to some of the objects as your little babies. They mean a lot to you.

YSYes. Sam Vawdrey, who was head of install for this show, found me laughing with Lisa Waup because I was telling the glass pieces off. They do have a life of their own. I feel like they have personalities, and they're all very different to each other. So during install, there was one plum with Granny Dinah (2016) who just wouldn't sit still. I actually said, 'Are you alright now?'

Yhonnie Scarce, Hollowing Earth (2017). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

DBIt's always amazing to see your work, but this is a particularly compelling installation, and the first room is just stunning. So congratulations to the entire team at ACCA for showing such respect for work that has such high integrity. Now, we've left some time for questions from the audience.

AUDI was wondering what you meant by Aboriginal architecture?

YSThere are eel traps, humpies, smoking trees, and scarred trees that are all a large part of our infrastructures and they're still standing. We're really lucky here in Victoria, that there's Budj Bim, which is in the Western districts of Victoria and has infrastructure, including eel traps, that's been sitting there for thousands of years and that shows how powerful it is.

Yhonnie Scarce, Only A Mother Could Love Them (2016). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

AUDIs there a contemporary Aboriginal architecture?

YSThere are not enough Aboriginal architects in Australia, I think. But there is Edition Office, and I've been talking about it at length, that there needs to be more Aboriginal architecture in Australia. Again, it's going back to acknowledging First Nations people; they should be doing that even with place names.

AUDThe bush plums are beautiful constructions, and I was struck by how flexible they are. They say so many things and in so many different ways. How long does it take to create an individual bush plum?

YSThe ones inside Missile Park probably take 20 to 30 minutes? Because they have black colouring. Clear ones would take less time than that. It doesn't take too long. But with yams and the smaller pieces, it's between 10 and 15 minutes. That's why I've got sore wrists, because they happen pretty fast, so there's a lot of moving.

DBIt's a physical practice.

YSIt makes you work hard alright. But I wouldn't do it if I didn't love it. Sweating it out is part of the process. That's the addictive part of it.

AUDI love the way you talk about found materials and what they mean, and what they bring to the work. Not just the images, but the objects as well. Could you talk a little bit about that?

Found objects and other materials are a large part of the process. I'm not a glass artist, I'm an artist who works with glass and other materials. Even though I'm primarily a glassblower, I like fossicking quite a lot and I like materials that have a life before me. Missile Park is from a scrap yard. Corey and I went to visit the scrap yard quite a lot. It's got a lot of memories from past lives. The holes in the sheds were actually there beforehand.

DBReally? You didn't do that?

YSNo. We may have added a few here and there but not as many as you think. So everything is pretty much pre-existing.

Yhonnie Scarce, Strontium: Fallout Babies (2016). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

DBThat is fascinating. We often talk about objects or places having identities; rivers or buildings holding memories. It's very much part of the way you work and think, too.

YSYeah, I think so. Depending on the work or research that I'm doing, or the ideas of a new work, sometimes the found object comes first. I like that part of uncovering what someone else has discarded.

AUDI think that would be present in the works that you exhibit, such as the trays for surgical instruments.

YSI think they're from the old Ballarat hospital here in Victoria. And it used to sit in someone's backyard down in Mornington Peninsula. So now they're elsewhere.

AUDWith the large hanging installation, there's a lot of movement and a bit of sound. I wonder whether that was purposeful?

YSNo, they do their own thing. With the three clouds, there's always some concern about air conditioning or the movement of human bodies within that space. But I think it's just part of what those clouds do, and I have no control over that whatsoever.

Yhonnie Scarce, Weak in colour but strong in blood (2014). Exhibition view: Yhonnie Scarce, Missile Park, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne (27 March–14 June 2021). Courtesy the artist and THIS IS NO FANTASY, Melbourne. Photo: Andrew Curtis.

DBThe cloud series comprises Thunder Raining Poison (2015), Death Zephyr (2017), and Cloud Chamber (2020). Using glass, you recreated the formation of clouds dispersing across the country, from photographs taken in the immediate aftermath of some nuclear explosions at Maralinga and also Emu Field.

YSThe first one, Thunder Raining Poison, was inspired by rainfall and the stories of people's skin burning, because they thought it was fluid from the sky, which it sort of was, but it was poisonous. And then Death Zephyr was inspired by wind and weather patterns. The image of the cloud that I found was moving close to the ground. So I call that one the death cloud, because it did engulf a lot of people.

Cloud Chamber was developed from that research that I touched on in Birmingham before I was sent home because of the pandemic. There's a little chamber that moves nuclear particles or uranium to create nuclear energy. So I thought about that with that cloud. But it is a direct reference to Breakaway, because I feel that the Breakaway bomb site was the monster.

Yhonnie Scarce, Death Zephyr (2017). Exhibition view: The National: New Australian Art, National Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (30 March–16 July 2017). Courtesy the artist.

AUDYou said that in South Australia, it is suspected that there have been a lot of massacres left unrecorded. Is that because of British military involvement?

YSProbably, yeah. But it seems to have happened before then. Information is just being uncovered now. But going back to the nuclear comment, the nuclear test was mass genocide. And that was just in a short amount of time. It's probably one of the biggest in Australia or South Australia in particular.

AUDI come from the U.K., and I used to work for the campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in London, which is where I met my Australian partner, which is why I'm here. But I wondered if you'd come across a group called the British Nuclear Test Veterans Association?

YSYes.

AUDAre they still out there?

YSOh, yeah. They are very active.

Yhonnie Scarce, Cloud Chamber (2020) (detail). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

DBMany of the people who worked out here during the British nuclear tests were obviously British personnel and many of them have survived, and can tell you stories about Emu Field and Maralinga. Even though there aren't very many atomic veterans left alive in Australia; there are more over there than there are here.

YSAnd they watch very closely. I think they've watched because both countries have issues with acknowledging the nuclear tests and how they killed people. They're fighting for that acknowledgement, so they are often in conversation with Australian veterans.

Yhonnie Scarce, Cloud Chamber (2020). Exhibition view: Looking Glass: Yhonnie Scarce and Judy Watson, TarraWarra Museum of Art, Tarrawarra (28 November–28 March 2021). Courtesy the artists.

AUDYou made some reference before about the histories of substances that you use. Where do you source the substances for the glass you blow?

YSIt's a batch from Castlemaine in Victoria. But there are other suppliers in Australia. There are people that make the silica and the other powder that goes with that to form the furnace glass. I used to get coloured glass from New Zealand, but they've moved their facilities to the U.S.

AUDI'm wondering whether you used actual sand from the site?

YSNo.

DBI think that's the question I asked you this afternoon, actually. It would be almost too much I think.

AUDI remember seeing your work Thunder Rain Poison at Defying Empire at the NGA (26 May–10 September 2017) a few years back. It was a very beautiful piece, but it was also incredibly terrifying at the same time. It made me think of how you dematerialise the object to lean towards the concept. I wanted to ask if you could speak more about your methodology in balancing aesthetic beauty with terrifying subject matter?

YSThe beauty about glass is that it has a sense of trickery. For me, glass was a beautiful material to use in order to bring people closer in to see the work. I have been told that people get closer to certain works, particularly Thunder Raining Poision (2015) or Blood on the Wattle (2013), and the coffin as well. They are very interested in the material but then quite disturbed by the story afterwards.

I like to be able to do that, because it's the material that I'm very much in love with, like Daniel said. It's something that I work with more closely. Particularly with the bomb clouds, it was always very strategic—to look from a distance, and you could get close, but not too close. It is about making you feel uncomfortable at the same time. —[O]

Yhonnie Scarce

https://www.artistprofile.com.au/yhonnie-scarce/