By Robert R. Shane

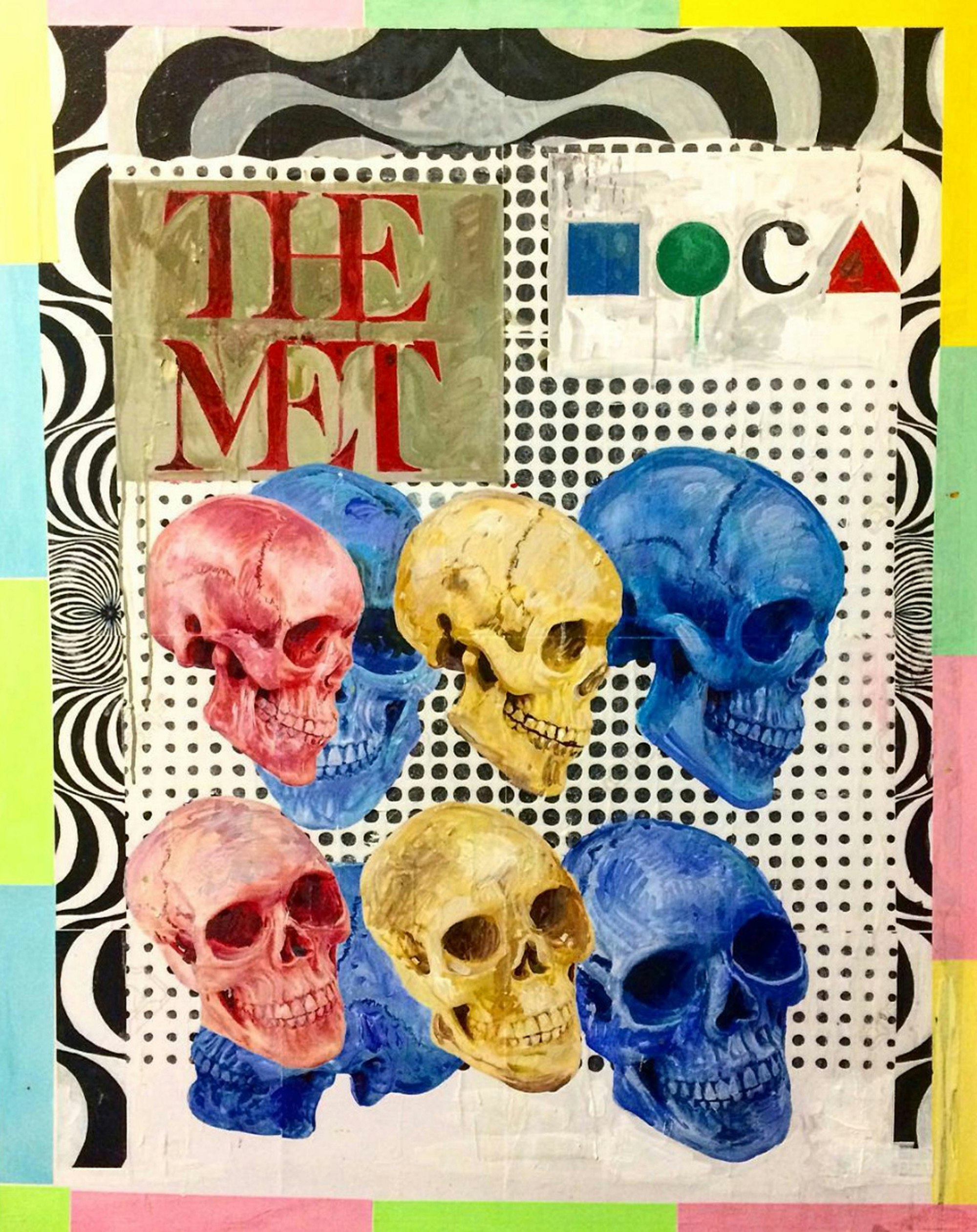

Noah Becker, Museum Skulls, 2018. Acrylic and mixed media on canvas, 40 x 30 inches. Courtesy the artist. American University Museum Mortality: A Survey of Contemporary Death Art

This is a review of an exhibition that never took place. Mortality: A Survey of Contemporary Death Art, originally slated for spring 2020 at the American University Museum, was cancelled when the institution shut down in response to the coronavirus crisis. Now the exhibition exists in memoriam in the catalog intended to accompany it. One year and a half million deaths since the COVID-19 outbreak began in the United States, Mortality has yet to be resurrected, though its themes could not be timelier. It provokes a conversation within our frequently death-denying, capitalist culture that is desperately needed, especially during the pandemic of which it was itself a casualty.

Highlighting images of the skull produced by 26 painters, sculptors, and photographers, Mortality revisits art historical tropes like the Vanitas and danse macabre that are contextualized by curator Donald B. Kuspit’s catalog essay. The skull, a universal symbol of death, resides inside me, Kuspit writes, as “an object hidden from sight until exposed to the light of day by death.” Today, one must ask how death is concealed from sight in the US: elder people hidden away and dying in nursing homes, the trauma witnessed by hospital staff but rarely seen in the media, the dead hidden away in refrigeration trucks. So many have been unwillingly sacrificed behind closed doors, just to keep the machine of economic production and consumption in motion.

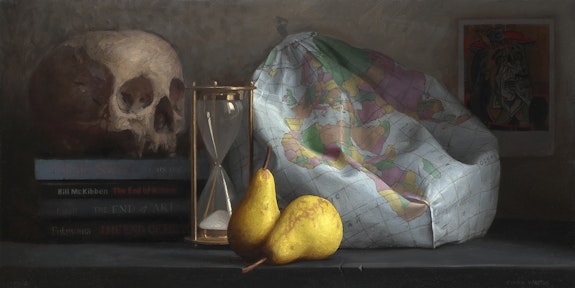

Conor Walton, It's the End of the World as We Know It, 2006. Oil on linen, 12 x 24 inches. Private Collection.

We see a critique of this situation reflected in Noah Becker’s and Conor Walton’s paintings, which reject the illusion that consumption, or even art, can transcend death. The gilded skull floating amidst Facebook and Apple icons, as well as an American flag, in Becker’s Tune Out #2 (2017) addresses the consumerist impulse to keep the anxiety of death at bay through distraction. Meanwhile, his Museum Skulls (2018), which features skulls in the primary colors floating over the logos of the Met and MOCA, dispels any hope that the legacy of art can conquer an artist’s death. Similarly, a skull lurks in the shadow behind a Mondrian composition fashioned from Lego blocks in Walton’s still life Lego Mondrian (2019). Deploying a collage aesthetic and luminous palette, Becker’s paintings function as a contemporary Vanitas, emblematic of the flat, hyper-paced world of the digital screen. Walton’s old master style also recalls traditional Dutch Vanitas, but with a contemporary update. A strong example is to be found in It’s the End of the World As We Know It (2009), which places a deflated plastic globe, perhaps foretelling climate disaster, alongside fruit, books, and, crucially, a skull and hourglass.

In addition to Vanitas, Mortality interrogates other traditional death tropes, such as “Death and the Maiden,” in which Death, represented as an emaciated man or skeleton, embraces a nude woman. Sonia Stark’s oil and pastel drawing Three Female Skulls, With Lipstick Smear (2020) offers a clever antidote to such morbid eroticization of women’s bodies. The title indicates that the horrific red field that bleeds into Stark’s three stacked skulls is merely a cosmetic stain, but it also genders the remains. Except to the trained eye of medical examiners and a few scientists, though, all skulls basically look the same. Thus, Stark’s piece hints at the absurdity of gendered death tropes.

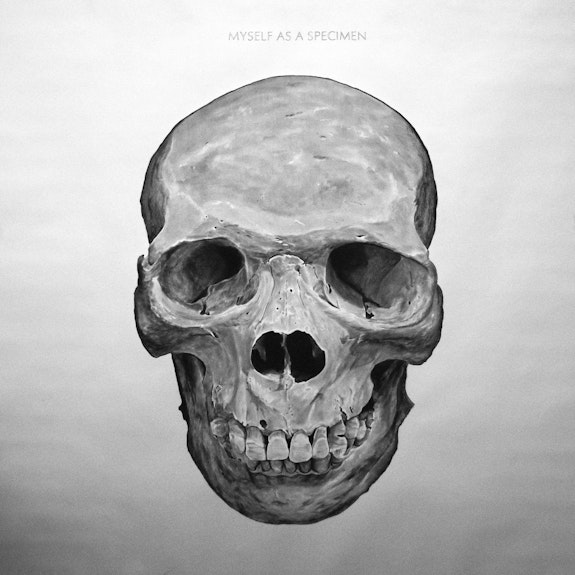

Trevor Guthrie, Myself as a Specimen, 2009. Charcoal, graphite on paper, 55 x 57 inches unframed. Private Collection.

Beyond its interest in the role played by death in artistic convention, Mortality also offers larger meditations on time and nihilism. In Jinsu Han’s chilling kinetic sculpture Dream Fiend 5C (2009) the human skull is reduced to junk in a steampunk nightmare. With a megaphone shoved in its mouth, it sits precariously atop a wheeled box. A black silhouette of a bird taps on the skull with clock-like precision, recalling the rapping of Edgar Allan Poe’s raven; its endless repetition mocks the finitude of human life. Trevor Guthrie considers his own finitude in the colossal Myself as a Specimen (2009), a frontal charcoal and graphite rendering of a skull on a sterile white background. Like St. Jerome in his study, Guthrie in his studio thinks through his death, but without the hope provided by scripture. Instead, his meditation is expressed by the demanding psychical process that underlies his painstaking, naturalistic technique. Decontextualized, as if on archeological display, this anonymous skull is a reminder that the specificity of its owner’s life will one day be forgotten. Lynn Stern demands similar contemplation from all of us in her photographic series of skulls draped in translucent black gauze. With exquisite detail and meditative light, these still compositions evoke silence and emptiness in the viewer. The seductive dark veils do not hide the skulls so much as draw us to them, as Stern asks each of us to become, like Trevor Guthrie, a modern-day St. Jerome.

Mortality: A Survey of Contemporary Death Art removes the veils we use to deny human fragility and the fear of death. Cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker argued in The Denial of Death that such veils operate as hero systems, giving us the illusion that we can transcend death. Indeed, as hospitals become overwhelmed with each wave of the pandemic, we confer on healthcare workers the mythic status of “hero.” The same rhetoric underlies other metaphors such as our “fight” or “war” against COVID, in which essential workers are “on the front lines.” Here in New York State the governor’s slogan “New York Tough” is meant to rally us around our common grit, but in truth we are New York vulnerable and, indeed, globally vulnerable. We must acknowledge this fact to properly care for and protect each other. A 21st century memento mori, Mortality offers a space to reckon with this vulnerability not through objects that stand as lasting tributes to their creators’ egos, but which show us how the ego can begin to face the reality of death.