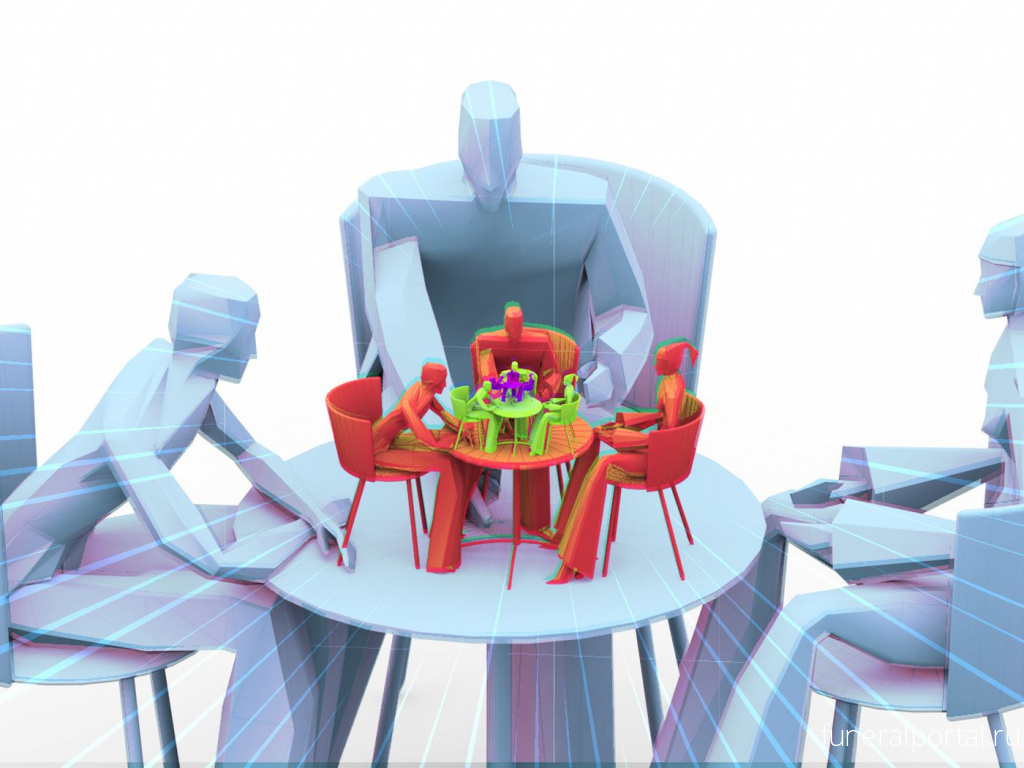

As viewers shelter with screens from the pandemic, more and more TV wrestles with mortality within digital reproductions.

“Are we living in a simulation?”

Before the recent troubles — that is, during the previous troubles — that saying was a popular quip, playing off the belief among some tech bigwigs and others that our universe is actually the workings of an elaborate computer program. Reality had become so bizarre, the joke was, it must be the product of glitchy software.

During the pandemic, it’s less of a dark-humored nerdism and more of a redundancy. What part of our lives are not simulations now? Warned away from the material world, we work in simulated office space, drink at simulated happy hours and trick out simulated islands in Animal Crossing.

We’re also spending more time with that old-fashioned virtual space, TV — which in turn has developed a recent obsession with stories set in simulated realities. These series appeal to anxieties about technology, but also to a deeper fear.

We are, let’s be blunt, suddenly thinking more often about death, the ultimate transition from the physical state. And death, as well as the possibility of other forms of life, is at the core of these stories.

Version 1.0 of this theme was Netflix’s dystopian “Black Mirror,” whose tales of digitized consciousness have built on the Plato’s Cave concepts of “The Matrix” and Philip K. Dick.

This was the basis of two of its more optimistic episodes, “San Junipero,” set in a software-generated afterlife, and “Hang the DJ,” in which people’s avatars lived a stupendous number of simulated love lives inside an online dating app. But more often, the “Mirror” creator, Charlie Brooker, imagined that if you could turn someone’s consciousness into code, you could use it to torture, to enslave or — more casually and frighteningly — to turn people into apps that could be switched off. Heaven may be a place on Earth, in the lyrics of the Belinda Carlisle song wryly used in “San Junipero.” But Hell fits neatly onto a microchip.

Since “Black Mirror,” virtual lives have been the subject of pulp series from NBC’s “Reverie” to Netflix’s “The I-Land.” But by some cosmic timing — or precise planning by the simulation! — there has been an influx of them just as the pandemic swept the globe.

Bespoke Realities

In “Devs,” Nick Offerman plays a tech mogul seeking to counteract the loss of his loved ones.Credit...Miya Mizuno/FX

Alex Garland’s “Devs,” which began in March on FX on Hulu, introduces itself as a haunting sci-fi thriller about tech hubris. Forest (Nick Offerman), a Silicon Valley mogul haunted by the death of his wife and young daughter, has built Devs, a supercomputer powerful enough to reproduce any past event (watch the first cave paintings in crystal-clear HD!) and flawlessly predict the future.

When I reviewed “Devs,” I couldn’t give away the final twist (so, fair warning): the real purpose of Devs is to cheat death, creating a fully simulated universe in which Forest’s loved ones do not die and into which his consciousness will be transferred. There is a god hidden in the machine. (Literally: The “v” in Devs is a Latin “u,” as in “deus.”)

In one sense, Forest is the latest in a line of Victor Frankensteins out to beat the Reaper. But Forest wants his arrogance to scale up: Not simply to stitch together a body but to fashion an entire, bespoke personal eternity — the eschatological equivalent of an oligarch’s floating seastead.

Garland, interestingly, does not give Forest a complete comeuppance, though things do not go entirely according to his plan. His plan, to have Devs create a single “reality,” fails; instead it generates countless multiverses. We leave him in one, reunited with his wife and daughter, but other versions of him exist in other simulations that, he says, are more like hell. His punishment, if you want to call it that, is to have to live in every future.

“Devs” had already shared themes with HBO’s rise-of-the-robots drama, “Westworld,” whose artificially intelligent androids populating violent theme parks were also essentially a byproduct of the effort to get a rich guy to evade death. Beyond the plot similarities, both stories were ultimately about whether a free world can exist if we can convert consciousness into lines of code.

But when “Westworld” returned in mid-March with a new setting for Season 3 — it decamped the parks for a tech-noir Los Angeles — it also had an eerily similar story line to “Devs,” involving simulated realities and a precognitive supercomputer with a quasi-religious name (the biblical Rehoboam).

Every Google must have its Bing, and neither show invented the concepts of artificial reality or determinism. But I preferred the slow, hypnotic and, sure, pretentious musings of “Devs” to the rebooted “Westworld,” which used its ideas mainly to set up another slalom course of story twists and whoops-it-was-all-an-illusion fakeouts.

A Privatized Afterlife

In “Upload,” Amell stars as a man spending eternity in a pricey digital afterlife.Credit...Katie Yu/Amazon Studios

If you’re cynical enough, and I am, one of the first things you think while watching either “Devs” or “Westworld” is, “Neat, but how do they monetize it?” (Those robo-parks in “Westworld” must have had a crazy burn rate, however rich their clientele.)

Greg Daniels, the co-creator of the American “The Office,” must be a kindred spirit, because his “Upload” posits that if humans built heaven, they would wring every last dime from it.

In this Amazon satire, science can back up human consciousness to disk before death, allowing people to spend eternity in one of several virtual luxury resorts — for a price. (Some people still believe in a religious afterlife, but those with the cash would rather not risk it. Mammon has taken God’s market share.)

For Nathan (Robbie Amell), the price is paid by his wealthy girlfriend, Ingrid (Allegra Edwards), who fast-talks him, as he slips away after a driverless-car crash, into making the ultimate commitment and spending eternity in Lakeview, the deluxe V.R. estate that her family has chosen as their private Elysium.

In Lakeview, Nathan finds a kind of Four Seasons nirvana with concierge service. His “angel,” Nora (Andy Allo), is a stressed-out service employee working from a high-tech call center, hoping to get her ill father into Lakeview on her employee discount. Naturally, she and Nathan develop an attraction, but it’s a romance complicated by a physical gap and the hierarchies of customer service.

Andy Allo in “Upload,” which envisions heaven as a corporate consumer experience with tiers and customer service representatives.Credit...Aaron Epstein/Amazon Studios

The human comedy of “Upload” is its weakest part. Allo is a charismatic colead, but most of the action has to be carried by Amell’s Nathan, who is too much of a generic Everyman to engage the imagination. “Upload” shines most in its world-building — which is all about world-building.

A privatized afterlife, the series argues, would become neither the hell of “Black Mirror” nor the paradise that Forest dreams of in “Devs.” It would just be one more tiered consumer experience, with white-glove service for the haves and low-data steerage for the masses, like a commercial-airline flight that never lands. (That this cautionary tale of the ultimate privatization of public experience streams on Jeff Bezos’s ecosystem is just the meta-cherry on top.)

All of which would resonate in any recent year. But coming to screens around the height of the pandemic, a comedy about death — and bridging the distance between the living and the digitized — had an unintended level of poignancy. In its imagined world, the living can interact with the digital dead, if only through screens or V.R. interfaces. What is that but the ultimate Zoom call?

Dreams of Death

“The Midnight Gospel” pairs trippy visuals with interviews from the podcast “The Duncan Trussell Family Hour.”Credit...Netflix

Resonant as it is, “Upload” treats death itself fairly lightly. For one of TV’s most profound explorations of what it is like to be a human living in the world with the knowledge that you and everyone you love will someday die, you need to turn to a cartoon full of mutants and zombie attacks.

“The Midnight Gospel,” an eight-episode series on Netflix, marries the hallucinogenic vision of Pendleton Ward (“Adventure Time”) with interviews of authors, spiritual guides and others that the comedian Duncan Trussell conducted for his podcast, “The Duncan Trussell Family Hour.”

“Midnight Gospel” is also nominally a sci-fi series involving artificial universes. Clancy (Trussell), a “simulation farmer,” uses a beat-up, womb-like biocomputer to visit alternative worlds and interview their weird denizens for his “spacecast.” But there is thankfully no pseudoscientific fig leaf justifying how this all works: The show simply asks you to drink from its bottle, Alice-like, and shrink or expand to its level.

It’s a disorienting transition. Most of the dialogue is verbatim interviews, playing over phantasmagoric images that serve as music to the show’s lyrics. In the first episode, Trussell talks to Dr. Drew Pinsky, the former “Loveline” host and addiction-medicine specialist, visualized as the president of an alt-Earth overrun by zombies. They have a meandering chat about the uses and abuses of drugs, while battling the undead and suffering the occasional disembowelment.

At this point you might think you know what the show is, a trippy work of stoner philosophy whose logic might go down better with a gummy. But “Gospel” begins to reveal its purpose in the next episode, in which Trussell/Clancy (in a chicken-headed avatar) chats with the memoirist Anne Lamott (in the form of a “deer dog”) about the death of her father and its effect on her, as they roll on a conveyor belt to a meat-processing plant to be turned into hamburger.

The hallucinogenic animation helps viewers detach from reality and engage with the spiritual.Credit...Netflix

The animation, by Titmouse, makes the fanciful “Adventure Time” look like photorealism. It can be disorienting, but the dream logic reveals itself. All the sanguinary gross-outs and philosophical musings are a kind of psychedelic modern equivalent of the danse macabre, the medieval art form that emerged after decades of war and plague, which depicted Death coming for king and peasant alike. No matter how grand or mean your station, the message was, memento mori: Remember that you must die.

“Midnight Gospel” sits with that knowledge and has weird fun with it. The mortician and author Caitlin Doughty, represented as the Grim Reaper, talks about the “death-industrial complex” that sold Americans on embalming. The writer Jason Louv, drawn as a “soul bird,” explains concepts from Buddhism, making an extended analogy between the “dream of life” and an immersive game like World of Warcraft.

All these conversations are piquant right now, when every day’s news invites you to imagine your death, or your loved ones’, untimely or accelerated. Yet unlike its live-action sci-fi peers, “The Midnight Gospel” is neither dystopian nor depressing. It’s uplifting and strangely beautiful, using its simulated universes — a “Yellow Submarine”-esque water world, a land run by teddy bears — as visual aids to detach the viewer from reality and to engage with the spiritual.

All this comes together in the astonishing final episode, made from recordings of Trussell and his mother, Deneen Fendig, before her death from cancer in 2013. Fendig, a psychologist, talks tenderly and lucidly about accepting her passing and tries to help her son accept it, too. “Turn toward this thing that’s called death,” she says. “Even if you’re afraid to turn toward it, turn toward it. It won’t hurt you. And see what it has to teach you.”

All the while, time passes. Clancy begins the interview as a baby, carried in his mother’s arms. As they speak, he grows up, she grows older and dies, then he births her as a baby, who ages with him until he’s a frail old man. They pass into space, turn into planets and drift toward the ends of the universe.

I worry that I’m making “The Midnight Gospel” sound like a downer. But it’s expansive and full-hearted and cathartic. I cried at it, but the good cry that you get from a work of art that makes you see the pain and joy and absurdity of fleshly existence as inseparable parts of the same miracle.

James Poniewozik is the chief television critic. He writes reviews and essays with an emphasis on television as it reflects a changing culture and politics.