By Sam Sacks

There is a hole in contemporary fiction that has been noticeable for some time but was especially conspicuous in this year. Novelists are obsessed with the apocalypse and have envisioned countless scenarios for the downfall of civilization. Equally, they are transfixed by grief and repeatedly are drawn to produce meditations on loss and recovery. But they do not like to write about the subtext of these preoccupations, the thing that they are hinting toward or circling around, cautiously evoking yet usually leaving off the page. They do not like to write about death.

How to write about something no one among the living has experienced? In his “Aspects of the Novel,” E.M. Forster observes: “There is scarcely anything that the novelist cannot borrow from ‘daily death’; scarcely anything he may not profitably invent. The doors of that darkness lie open to him and he can even follow his characters through it, provided he is shod with imagination.” The novelist’s inherent ignorance is in fact the source of unmatched artistic possibility, and when we think of the most enduring writers we can nearly always match them with an unforgettable death scene. The death may be noble, like Sydney Carton’s in “A Tale of Two Cities,” or wretched, like Madame Bovary’s; it may be romantic, like Dr. Zhivago’s, or hideously meaningless, like the suffering child’s in Camus’s “The Plague”; but it is always present.

Such scenes are the exception now, implied but rarely confronted, and in this reticence, I think, literature is running downstream from culture at large. Western society, having insulated itself from the reality of death more successfully than any collection of people in human history, is uncomfortable with reminders of its inevitability. Death has become as we imagine sex was to the Victorians: a taboo, unsuitable for mixed company—one of the last unmentionable subjects.

Much of our perceived immunity to death disappeared in 2020, and so far as that affected reading habits, it was perfectly reasonable to want books that provided the escapism that had become harder to find in real life. I felt that too. But amid the tensions and anxieties, the uninterrupted blare of ambulance sirens, the close calls and the tragedies, I also found myself searching for books that looked plainly at death, even as I rearranged my life to elude it.

Echoing Plato and Cicero, Montaigne famously declared: “To philosophize is to learn how to die.” “To begin depriving death of its greatest advantage over us,” he wrote, “let us adopt a way clean contrary to that common one; let us deprive death of its strangeness; let us frequent it, let us get used to it; let us have nothing more often in mind than death.” Literature can help us with this as well. In his novel “My Red Heaven,” which was published in January, before most people could have foreseen the shape the year would take, Lance Olsen puts the matter more imperatively: “Art doesn’t make life more bearable or longer or impervious to anguish. Its real goal is the opposite: to teach you that nobody can be saved in the end.”

These were the books, then, that for me best addressed the moment. Sometimes the reminders had political ramifications. Phil Klay’s “Missionaries” moves among battlefields in Afghanistan, Colombia and Yemen, dramatizing the perpetual warfare waged in the name of peacekeeping. But though the novel assumes a global perspective, it is always developing characters who live amid crossfire and drone strikes, vividly underscoring the fact that foreign policy is paid for with the lives of innocents. Life is similarly tenuous in Ge Fei’s “Peach Blossom Paradise,” set in revolutionary China at the turn of the 20th century. In its quiet, dreamlike fashion, the historical saga belittles all pretensions to power, summarizing the tawdriness of political violence in a single maxim: “When the big cats fight, the little deer die.”

Paul Lynch’s “Beyond the Sea,” about two men marooned on a broken fishing boat in the Pacific Ocean, stages a more personalized confrontation with death while retaining the mythic elements of a fable. In lean, sun-cured prose, Mr. Lynch’s fishermen debate the virtues of survival or acquiescence to fate, a hypnotic embellishment on the cosmic question “To be or not to be?”

The loss of a loved one is a recurring catalyst in contemporary fiction, but two novels in particular dispersed the fog of sentiment that often obscures it. Yaa Gyasi’s “Transcendent Kingdom,” about a young woman’s struggle to make sense of her brother’s death from a drug overdose, is rigorously forensic in its scrutiny of both the consolations of religion and the explanations of biology. Small revelations fly like sparks from an anvil; Ms. Gyasi arrives at no clear answers, but the brilliance and tenacity of her inquest provide their own justification. Narrative uncertainty abounds in Percival Everett’s “Telephone”—three slightly different versions of the novel were published simultaneously—but not as concerns the central tragedy, a daughter’s slow demise from cancer. In this wise, melancholic work, the death of a child is an irreducible truth beside which all else is contingent, an iron sadness that exists at the core of everything.

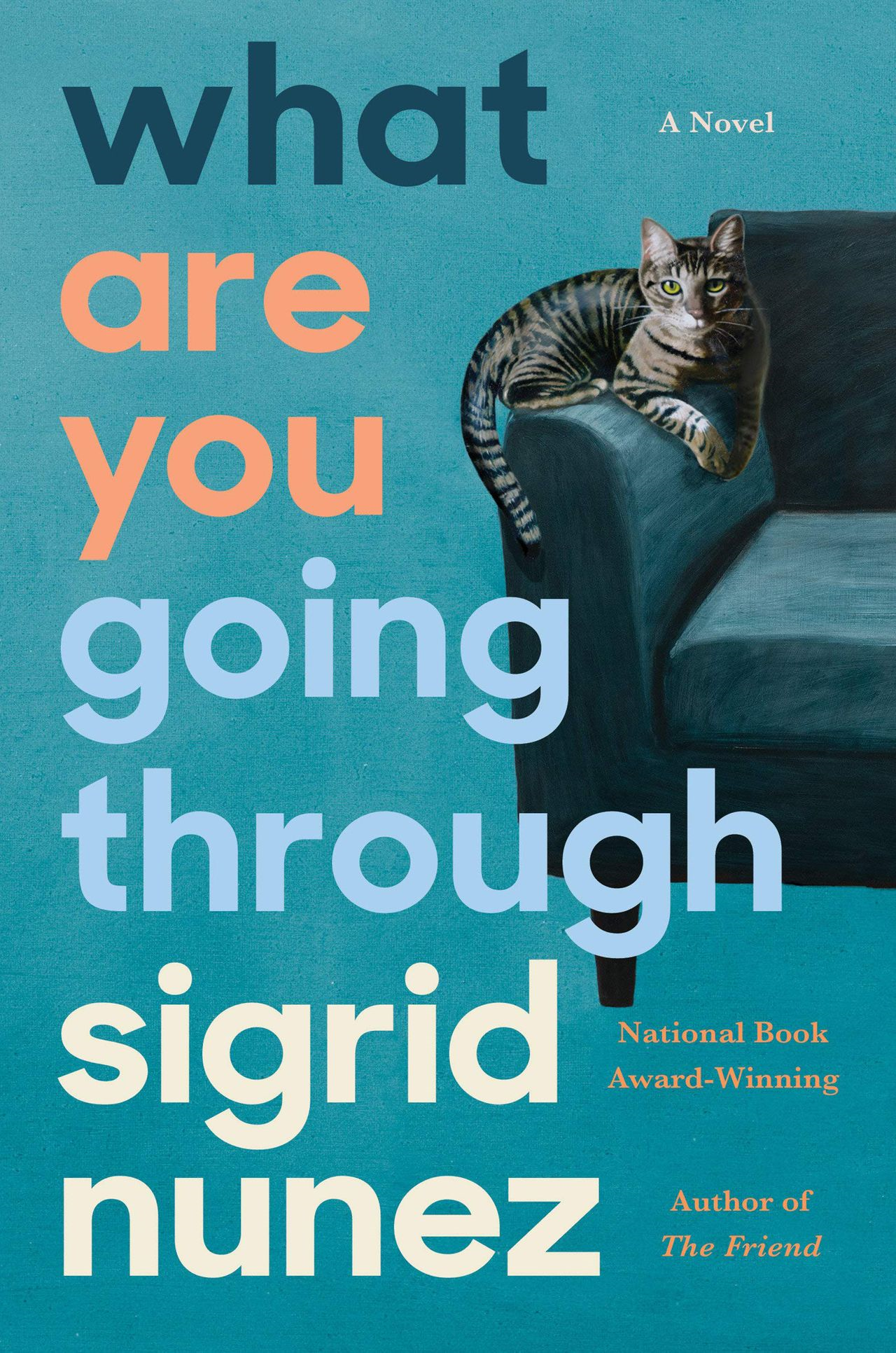

“In a new book I’ve been reading, I find someone comparing the experience of watching a person die with the intensity of falling in love,” says the narrator of Sigrid Nunez’s “What Are You Going Through.” The narrator has agreed to go to a vacation house with a friend who is succumbing to cancer and keep her company until that friend takes a euthanasia drug, and though you would expect the story to be morose, Ms. Nunez has filled it with laughter, bookish curiosity and passionate affection. There is euphoria in finality, the friends discover. Life, like this intimate, strangely disarming novel, becomes sharp and exquisite.

And it is to awaken us to our lives, of course, that we need memento mori. Lawrence Durrell wrote that “if art has any message it must be this: to remind us that we are dying without having properly lived.” A street preacher prophesying Armageddon appears in the opening pages of Christopher Beha’s “The Index of Self-Destructive Acts.” The novel soon moves on to chronicle the troubles common to well-groomed realist fiction—white-collar crime, social striving, adultery—yet the preacher remains on the fringes, a disturbance to the story’s smooth texture. As the date he has assigned to the apocalypse approaches, an acolyte puts up billboards with the words “What would you change if you knew it was all going to end?” The question, once planted in the characters’ minds, brings about unforgettable reckonings. If I have one wish for the novels of the coming years, it’s that they keep on asking it.

Memento Mori, Memento Vivere. Use an exercise about death to help you live a better life.

https://medium.com/the-ascent/memento-mori-memento-viveri-8df26bd2aad8